Oak Toad

Anaxyrus quercicus

Common Name: |

Oak Toad |

Scientific Name: |

Anaxyrus quercicus |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Anaxyrus is Greek meaning "A king or chief" |

Species: |

quercicusis derived from the Latin word quercinus, which means "of oak leaves". This pertains to the general oak leaf like color and pattern of the toad |

Average Length: |

0.75 - 1.3 in. (1.9 - 3.3 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

|

Record length: |

Virginia Wildlife Action Plan Rating Tier II (Very High Conservation Need) - Has a high risk of extinction or extirpation. Populations of these species are at very low levels, facing real threat(s), or occur within a very limited distribution. Immediate management is needed for stabilization and recovery.

Physical Description - This species is small, with lengths ranging from 0.75-1.25 inches (19-33mm). The background color on this species ranges from gray to nearly black. It has a conspicuous light mid-dorsal stripe that is white, cream, yellow, or orange. On individuals with a lighter background color, 4-5 pairs of dark spots may be visible on the back. The skin is finely roughened with tubercles. The bottoms of the fore and hind feet have reddish, orange tubercles. The male vocal sac is oval or sausage-shaped when inflated. Sexual dimorphism is not strong.

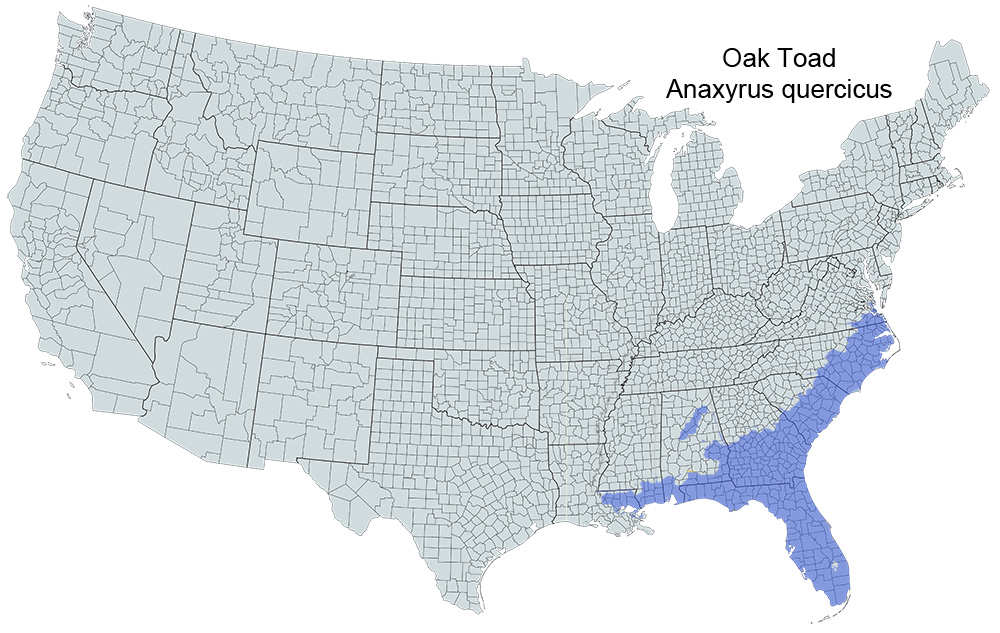

Historical versus Current Distribution - Oak toads (Anaxyrus quercicus) range from the Coastal Plain of southeast Virginia, west to Louisiana. They are found throughout Florida and on some of the lower Florida Keys (Conant, 1975; Dalrymple, 1990; Dodd, 1994; Behler and King, 1998). Their current range has been extended since the early description by Holbrook (1842; see Duellman and Schwartz, 1958; Ashton and Ashton, 1988).

Historical versus Current Abundance - Oak toads are abundant in southern pine wood habitats. Wright (1932; Wright and Wright, 1949) reported as early as 1921 that they were locally abundant in the Okefenokee Swamp (Georgia). Their local abundance was also reported in several locations in Florida (in 1895) and Louisiana (in 1923; Wright and Wright, 1949; Hamilton, 1955). In subtropical Florida, these toads are most common in low elevation pinelands (Dodd, 1994). They remain abundant in undisturbed preferred habitats throughout their range. However, due to rapid human development throughout much of the south and concomitant habitat destruction, as well as the introduction of exotic species via the pet trade (Meshaka, 2003), their numbers can be expected to steadily decrease (Wilson and Porras, 1983).

Breeding - Reproduction is aquatic.

Breeding migrations - Mating occurs from April–October, with peak activity in the early spring (Harper, 1931; Einem and Ober, 1956). Heavy, warm spring rains stimulate mating behavior (Wright and Wright, 1949). Males typically call from flooded fields, the edges of ponds and puddles, and from clumps of understory vegetation (Dalrymple, 1990). Oak toads are distinctive in that they are primarily active during the day (Dalrymple, 1990), although both daytime and nighttime breeding has been observed (Punzo, 1992a). Most adults are collected during the summer throughout their range, whereas juveniles are most active during late summer and early autumn (Dodd, 1994).

Breeding habitat - Oak toads prefer shallow pools, cypress and flatwood ponds, and ditches. Eggs are usually attached to grass blades 4–12 cm beneath the surface of the water (Hamilton, 1955; Ashton and Ashton, 1988). Following breeding, adults exhibit a y-axis orientation to exit ponds, suggesting animals use celestial cues to navigate (Goodyear, 1971).

Egg deposition sites - The eggs are laid in strings or bars that are typically attached to vegetation; each string contains 3–8 eggs (Wright, 1932).

Clutch size - Females typically lay 300–500 eggs, each approximately 1 mm in diameter (Hamilton, 1955; Dodd, 1994). Embryos usually hatch from 24–36 hr after fertilization.

Altig & McDiarmid 2015 - Classification and Description:

- Eastern Linear

- Arrangement 3 - Eggs oviposited as strings.

- Sub-arrangement A - Jelly tube unilayered and diaphanous, difficult to see; string short Eggs deposited in ephemeral, non-flowing water; Ovum Diameter about 0.8-1.0 mm; tube diameter 1.2-1.4 mm; partitions between uniserial ova.

- Arrangement 3 - Eggs oviposited as strings.

Larvae/Metamorphosis - Oak toad tadpoles reach a maximum length of 18–19.4 mm at stage 41 in 4–5 wk, and toadlets range from 7.2–8.9 mm SVL (Volpe and Dobie, 1959). Tadpoles are non-selective filter feeders and ingest a diverse array of algae as well as decaying animal material (Dalrymple, 1990).

Tadpoles:

| Lateral View | Dorsal View |

|---|---|

| BL = Body Length | IND = Internarial Distance |

| MTH = Maximum Tail Height | IOD = Interorbital Distance |

| TAL = Tail Length | TMW = Tail Muscle Width |

| TL = Total Length | |

| TMH = Tail Muscle Height |

Juvenile Habitat Same as adult habitat.

Adult Habitat Oak Toads are most often associated with open canopied oak and pine forests containing shallow temporary ponds and ditches (Duellman and Schwartz, 1958; Dodd, 1994) and wet prairies, characterized by short hydroperiods, of the southeastern coastal plain (Hamilton, 1955; Pechmann et al., 1989). Oak Toads prefer areas without permanent water and well- to poorly drained soils. They commonly seek refuge under boards and logs or in shallow depressions or burrows surrounded by vegetation, including cabbage palms (Sabal palmetto) and saw palmettos (Serenoa repens; Hamilton, 1955; Duellman and Schwartz, 1958). The minimum habitat area has not been delineated for Oak Toads (Dalrymple, 1990), however, an earlier study by Hamilton (1954) suggested that an area as small as 1 ac could sustain a breeding population.

Home Range Size - Unknown.

Territories - Unknown.

Aestivation/Avoiding Dessication - During the winter in the northern part of their range, Oak Toads remain underground in burrows and shallow depressions for intermittent intervals depending on ambient temperature conditions (Harper, 1931; Wright and Wright, 1949). During cold weather they have also been found in rotten oak logs and under pine bark (Hamilton, 1955).

Seasonal Migrations - During heavy rains, adults will move up to 80 m from refuge sites to breeding ponds (Wright, 1932; Dodd, 1994).

Torpor (Hibernation) - May hibernate from early December to early March (Harper, 1931).

Interspecific Associations/Exclusions - Unknown.

Age/Size at Reproductive Maturity. Oak Toads are the smallest toads in North America, with an adult body size ranging from 20–26 mm SVL for breeding males and 24–30 mm for females (Hamilton, 1955). Age at first reproduction is 1.5–2.3 yr (Ashton and Ashton, 1988; Dalrymple, 1989).

Longevity - Oak Toads are known to live 4 yr (Wright, 1932; Ashton and Ashton, 1988).

Feeding Behavior - Adults are insectivorous with a strong preference for ants (Punzo, 1995). Adults also feed on beetles, lepidopterans, aphids, dipterans, orthopterans, spiders, pseudoscorpions, centipedes, and mollusks (Duellman and Schwartz, 1958; Punzo, 1995). Juvenile diets include a high percentage of collembolans, ants, small spiders, and mites (Crosby and Bishop, 1925; Punzo, 1995).

Predators - A number of animals have been observed attacking (and in some cases killing and ingesting) Oak Toads, including raccoons, crows, hog-nosed snakes (Heterodon sp.), garter snakes (Thamnophis sp.), gopher frogs (Lithobates capito), and Marine Toads (Anaxyrus marinus; Harper, 1931; Wright, 1932; Hamilton, 1954).

Anti-Predator Mechanisms - As with many other bufonids, Oak Toads will inflate their bodies (unken reflex) when confronted by potential snake predators (Duellman and Trueb, 1986; Heinen, 1995). They also are capable of secreting toxins from the parotoid glands (Licht, 1967c). Their eggs appear to possess some toxic properties (Licht, 1968).

Diseases - Unknown.

Parasites- Nematodes of the genera Oxysomatium and Oswaldocruzia are reported to parasitize Oak Toads (Hamilton, 1955).

Conservation - Virginia Wildlife Action Plan Rating Tier II - Very High Conservation Need - Has a high risk of extinction or extirpation. Populations of these species are at very low levels, facing real threat(s), or occur within a very limited distribution. Immediate management is needed for stabilization and recovery.

References for Life History

- AmphibiaWeb. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA.

- Conant, Roger and, Collins, John T., 2016, Peterson Field Guide: Reptiles and Amphibians, Eastern and Central North America, 494 pgs., Houghton Mifflin Company., New York

- Duellman, William E. and, Trueb, Linda, 1986, Biology of Amphibians, 671 pgs., The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

- Martof, B.S., Palmer, W.M., Bailey, J.R., Harrison, III J.R., 1980, Amphibians and Reptiles of the Carolinas and Virginia, 264 pgs., UNC Press, Chapel Hill, NC

- Mitchell, Joseph C. and Karen K. Reay, 1999, Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles in Virginia, Num. 1, 122 pgs., Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, Richmond, VA

- Terwilliger, K.T., 1991, Virginia's endangered species: Proceedings of a symposium. Coordinated by the Virginia Dept. of Game and Inland Fisheries, Nongame and Endangered Species Program, 672 pp. pgs., McDonald and Woodward Publ. Comp., Blacksburg, VA

- Wilson, L.A., 1995, Land manager's guide to the amphibians and reptiles of the South, 360 pp. pgs., The Nature Conservancy, Southeastern Region, Chapel Hill, NC

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence

Greensville

Isle of Wight

Southampton

Surry

Sussex

CITIES

Suffolk

Verified in 5 counties and 1 cities.

U.S. Range