Broad-headed Skink

Plestiodon laticeps

Common Name: |

Broad-headed Skink |

Scientific Name: |

Plestiodon laticeps |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Plestiodon is derived from the Greek words pleistos meaning "most" and odontos meaning "teeth". Plestiodon = Toothy Skinks. |

Species: |

laticeps is derived from the Latin word latus meaning "broad" and Latin suffix ceps meaning "head". |

Average Length: |

6.5 - 12.8 in. (16.5 - 32.4 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

11.3 in. (28.7 cm) |

Record length: |

12.8 in. (32.4 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Scincus laticeps in 1801 by Johann Gottlob Theaenus Schneider, based on a specimen without locality data in the Museum of Gottingen in Germany. The holotype is now lost. Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to Charleston, South Carolina. The genus Eumeces was first used for this species by Peters (1864). Taylor (1935) pointed out that the names Pleistiodon erythrocephalus (Holbrook, 1842), and Eumeces quinquelineatus, used by Cope (1900) for several Virginia specimens, were synonyms of P. laticeps. Until Taylor's redescription (1932b), this skink was often confused with the two other species of Pleistiodon that occur in Virginia (e.g.. Hay, 1902). Taxonomy for Plestiodon (often as Eumeces) follows Taylor (1935, Univ. Kansas Sci. Bull. 23: 1–643) and Brandley et al. (2012, Zool. Jo. Linn. Soc. 165: 163–189). Richmond (2006, Evol. Dev. 8: 477–490) found a substantial division between mtDNA haplotypes of eastern and western P. laticeps but did not draw any taxonomic conclusion from it. No subspecies are recognized.

Description: A large skink reaching a maximum snout-vent length (SVL) of 143 mm (5.6 inches) and a maximum total length of 324 mm (12.8 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known SVL is 122 mm (4.8 inches) and maximum total length is 287 mm (11.3 inches). Tail length in the Virginia sample was 44.1-62.4% (ave. = 58.3 ± 4.2, n = 18) of total length.

Scutellation: Body scales smooth, shiny, and overlapping; scale rows around midbody 28-32 (ave. = 30.8 ±1.2,n = 21); scale rows around tail 10 scales posterior to anal opening 16-20 (ave. = 17.4 ±1.0,n = 19), 84.2% of sample is > 16; mid-ventral row of subcaudal scales wider than long relative to adjacent scales; supralabials 8/8 (52.2%, n = 23), 8/7 (40.4%), or 7/7 (17.4%); posterior labial scale touching crescent-shaped temporal scale located above ear opening (38.6%, n = 44; sides counted separately), separated from it by 1 or 2 small scales (52.3%), or separated from it by another temporal scale (9.1%); labial scales between rostral and first supralabial entering eye (= preorbital supralabials) 5/5 (53.1%, n = 49), 4/5 (34.7%), or 4/4 (12.2%); postnasals present; mental single; postmentals 2

Coloration and Pattern: Five narrow, white to cream stripes on dark-brown, grayish-brown, or black background; some individuals all brown and lacking stripes (see "Sexual Dimorphism"); sublateral light stripe may be present, forming a total of 7 stripes; head usually dark with reddish-orange stripes in juveniles and reddish orange with no or faded stripes in adults; lateral dark fields usually darker than dorsolateral fields, especially on adults; light stripes and dark fields between them extend onto tail for at least half its length (complete tails only); middorsal stripe forks behind head, and branches reunite on rostrum; dorsolateral stripes originate above eyes and extend posteriorly along scale rows 3-4 (counting from middorsal line), both rows usually involved; lateral stripes originate on supralabial scales below eyes and pass through ear openings and above insertions of forelimbs and hind limbs; below this line, dorsal background color fades into lighter ventral color; light stripes on adults often bordered by thin black lines; chin, anterior venter, ventral surface of limbs, and midventral subcaudal scale row cream; venter between limbs cream to gray-blue; original tail with 5 light stripes that fade distally into a uniform gray-brown; regenerated tail brownish or grayish.

Sexual Dimorphism: Adult males (103.3 ± 12.5 mm SVL, 76-122, n = 26) averaged significantly larger than females (94.9 ±8.6 mm SVL, 80-112, n = 15). Sexual dimorphism index was -0.09. The heads of adult males were wider (13.3-26.6 mm, ave. = 20.9 ± 3.9, n = 26) than those of adult females (12.7-20.3 mm, ave. = 15.4 ± 1.8, n = 13). Vitt and Cooper (1985a) demonstrated that this difference remained after the covariation due to body size was removed. Tail length relative to total length (males 54.7-61.5%, ave. = 59.2 ± 2.4, n = 9; females 44.1-61.1%, ave. = 55.3 ± 6.6, n = 5), scale rows around midbody (males 30-32, ave. = 30.6 ± 0.7, n = 8; females 29-32, ave. = 31.1 ± 1.2, n = 9), and scale rows around the tail 10 scales posterior to the anal plate (males 16-19, ave. = 17.0 ± 1.0, n = 8; females 17-20, ave. - 17.7 ± 1.0, n = 9) were not sexually dimorphic.

Adult males lose the body and tail stripes with age, becoming uniformly brown with a brownish-gray tail. The head in males becomes bright orange and enlarged in the temporal region during the mating season (spring) but fades and reduces in size in other times of the year. Females lack the enlarged orange heads and retain the stripes for life, although they do fade somewhat.

Juveniles: Juveniles are black to dark brown at hatching, with light-orange head stripes and cream-to-orange-tinted body stripes. Sublateral light stripes may be present. The stripes on the tail are blue. The blue tail color is usually retained until sexual maturity is reached (about 75-80 mm SVL). Size at hatching in Virginia P. laticeps averaged 32.1 ± 2.2 mm SVL (28-35, n = 14) and 75.9 ± 5.2 mm total length (65-82, n = 10). Body mass at hatching is unknown.

Confusing Species: Plestiodon laticeps may be confused with P. fasciatus and P. inexpectatus. The dorsolateral body stripe on the latter species occurs on scale rows 4-5 (counting from the midline of the dorsum), and the midventral subcaudal scale row is not enlarged. Plestiodon fasciatus is not easily separated from P. laticeps because there is considerable overlap in scale characters and both are colored and patterned similarly. Adult individuals of P. laticeps (80 mm SVL) are larger than those of P. fasciatus (<79 mm SVL). The combination of number of preorbital supralabials (usually 4/4 for P. fasciatus), the posterior labial-temporal scale configuration (see "Descriptions"), and the number of scale rows around the tail 10 scales posterior to the anal plate (most P. fasciatus have 14-16) are reasonably reliable characters for separating these two species. The tail of P. laticeps usually retains the blue coloration until maturity is reached (about 76 mm SVL), whereas the blue color is absent in individuals of P. fasciatus larger than 52-55 mm SVL. Sublateral light stripes are present in some specimens of P. laticeps.

Geographic Variation: The small sample sizes available from Virginia preclude analyses of geographic variation in this species. Davis (1968) examined large samples and noted several differences in scale characters among broad regions.

Biology: Broad-headed Skinks are largely arboreal and, in Virginia, inhabit open forested areas. They are most common in open, mature pine stands and in open stands of mixed hardwood-mostly live and turkey oak and loblolly and Virginia pines. They have also been found on houses and barns in wooded areas. In South Carolina, these skinks were most abundant in stands of live oak (Vitt and Cooper, 1985a, 1985b). This skink prefers a more xeric habitat than P. fasciatus. All of the known Virginia specimens were collected April through August. Winter aggregations in underground retreats were found in Alabama (Cooper and Garstka, 1987). The seasonal activity of this skink and the nature of its changes in habitat use between seasons are unknown.

Plestiodon laticeps is a predator of a wide variety of invertebrates and some vertebrates. The prey of this lizard in Virginia is unknown. In Maryland, McCauley (1939) reported orthopterans, hymenopterans, spiders, and a Five-Lined Skink (P. fasciatus) as prey of this species. In South Carolina, Vitt and Cooper (1986b) recorded the following prey types: grasshoppers, crickets, roaches, various forms of beetles, earwigs, true bugs, lepidopteran larvae and moths, flies, ants, horntails (a hymenopteran), amphipods, spiders, pill bugs, harvestmen, pulmonate snails, and lizards, including juveniles of their own species. Many of the prey types eaten indicated that Broad-headed Skinks foraged in and under the leaf litter, as well as when they were in trees. Thus, this skink uses both chemosensory and visual cues to detect prey (Vitt and Cooper, 1986b) and spends more time on the ground than we had once thought. Prey are often grabbed behind the head and subdued; the point of attack is determined by the contrast of the head and thorax colors or the movement of the prey (Cooper, 1981). Natural predators of this large skink are unknown. Introduced domestic cats kill an unknown number each year (Mitchell and Beck, 1992).

Female P. laticeps are oviparous and lay a single clutch of eggs in decaying logs and stumps in June. Vitt and Cooper (1985b) noted that a nesting female will circle around her eggs in the decaying portion of a log or stump and pack the debris around the cavity she made in order to form a nest. If she leaves the nest, she simply pushes an opening in the debris wall. Upon return, she circles around the eggs again, thus closing the opening. Mating has been observed in Fairfax County on 7 June (C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). Vitt and Cooper (1985b) observed courtship in South Carolina on 13 May. Males and females mature at about the same size (Vitt and Cooper, 1985a). The smallest mature male I measured was 76 mm SVL and the smallest mature female was 80 mm SVL. Virginia females were found tending nests in Virginia on 28 June, 5 July, and 16 July. A female captured on 19 June deposited a clutch of eggs on 23 June. They hatched on 18 July, an incubation period of 25 days. Other laboratory hatching dates are 11 and 16 August. Clutch size in Virginia was 9-13 (ave. = 11.8 ± 1.9, n = 4). Eggs averaged 15.8 ± 1.9 x 11.6 ± 1.7 mm in size (length 11.1-19.0, width 9.5-14.5, n = 42) and weighed 0.917-0.965 g (ave. = 0.941, n = ave. of two clutches).

The population ecology of this species is unknown. Large adult males in South Carolina guard their territories and the females within them, chasing smaller males away (Vitt and Cooper, 1985a). This behavior suggests that territory placement is dependent on the availability and spacial distribution of appropriate trees and perch and nesting sites. Thus, population sizes may be regulated by the structure of the habitat. Adults of this species are probably the longest lived of any Virginia lizard. Cooper and Vitt (1987a) noted a male they collected in South Carolina had a potential life span of over 8 years.

Broad-headed Skinks usually escape from potential predators, such as humans, by climbing high in trees and entering tree cavities. They are known to swim during an escape and will also seek refuge under terrestrial debris. They can bite hard when caught. Adult males are particularly aggressive to other males during the mating season. Males visually recognize other adult males by the presence of the bright orange heads and females by the lack of it (Cooper and Vitt, 1988). The orange color is regulated by the seasonal production of the male hormone testosterone (Cooper et al., 1987). Females emit a pheromone from glands in the base of the tail during the short time they are sexually receptive and males can find them by tracking their chemical trails through tongue-flicking the substrate (Cooper and Vitt, 1986b). The pheromone stimulates male courtship behavior (Cooper et al., 1987). Recognition of other species of Plestiodon is achieved primarily by detecting chemical cues in their trails (Cooper and Vitt, 1986a). The function of the blue tail in juvenile P. laticeps is the same as described in the P. fasciatus account.

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are big scorpion lizard (Dunn, 1936) and greater five-lined skink (Carroll, 1950; Schmidt, 1953; Reed, 1957b).

Conservation and Management: Plestiodon laticeps is not a species of special concern in Virginia because of its wide distribution. In areas of urban development, however, this lizard will have difficulty surviving because of the loss of open wooded stands large enough to support viable populations, and because of mortality from humans and domestic cats. Conservation of this element of Virginia's biodiversity is best approached by the management of large, open wooded areas with mature and dead trees within them, and by control of predation by cats.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Cumberland

Fairfax

Fauquier

Fluvanna

Franklin

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Isle of Wight

James City

King George

Lancaster

Loudoun

Montgomery

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Scott

Shenandoah

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Warren

Westmoreland

York

CITIES

Chesapeake

Newport News

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Verified in 48 counties and 5 cities.

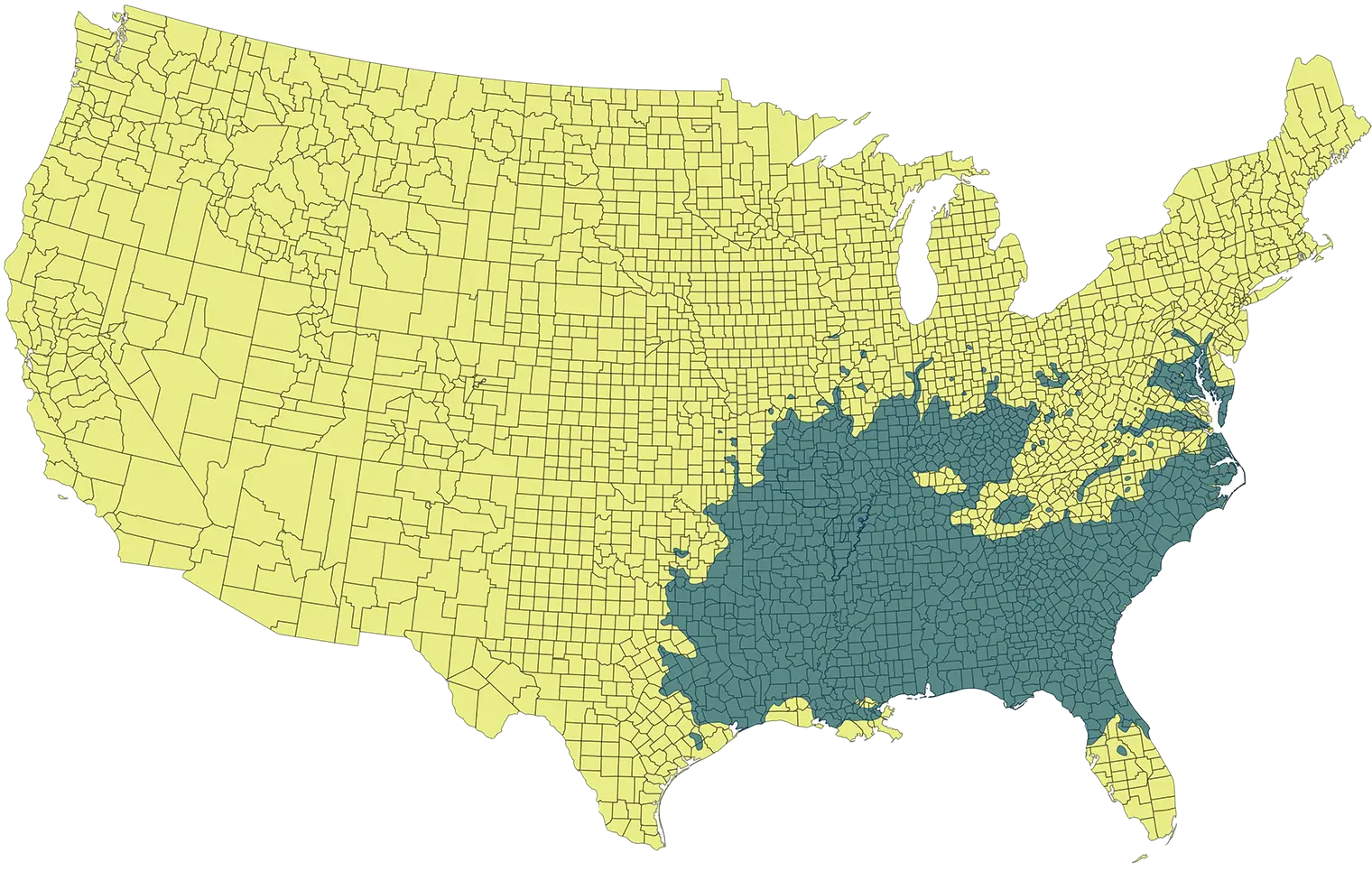

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.

001 copy_small1.jpg)