Red Cornsnake

Pantherophis guttatus

** Harmless **

Common Name: |

Red Cornsnake |

Scientific Name: |

Pantherophis guttatus |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Pantherophis |

Species: |

guttatus is derived from the Latin word gutta which means "dappled" or "spotted" referring to the dorsal pattern. |

Vernacular Names: |

Beech snake, bead snake, brown sedge snake, chicken snake, fox snake, house king snake, mole catcher, mouse snake, pine snake, red rat snake, red chicken snake, spotted snake, spotted racer, spotted viper. |

Average Length: |

30 - 48 in. (76 - 122 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

56.7 in. (144.4 cm) |

Record length: |

72 in. (182.9 cm) |

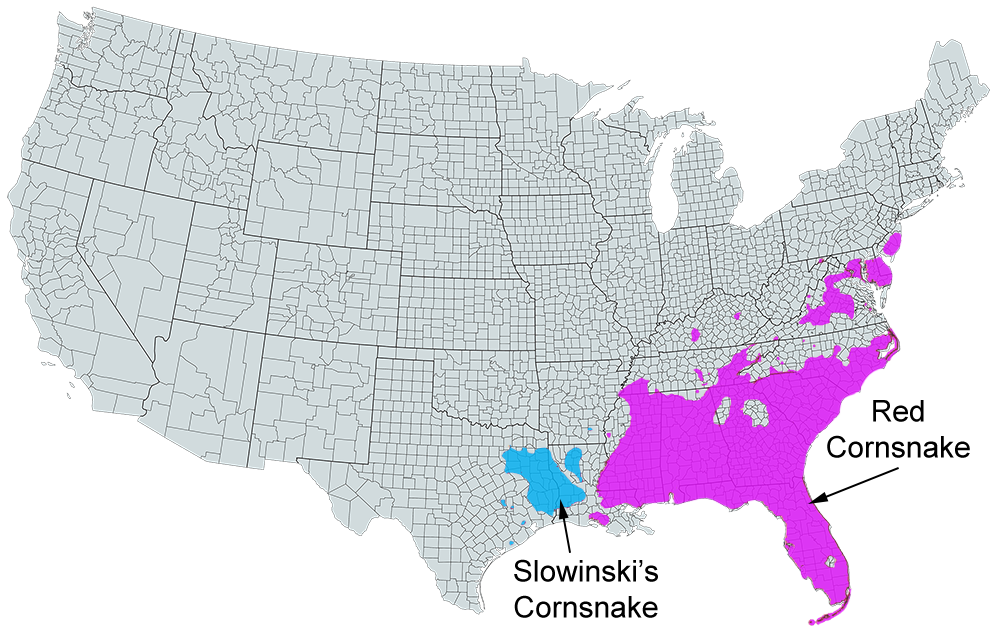

Systematics: Carolus Linnaeus originally described this species as Coluber guttatus in 1766 from a specimen sent to him from "Carolina" by Alexander Garden. The type locality was later restricted to Charleston, South Carolina, by Dowling (1952). Dunn (1915a) was the first to use the genus Elaphe for this species but spelled the specific name guttatus. In the Virginia literature, Cope (1900) used Coluber guttatus for this species and Hay (1902) used Callopeltis guttatus, apparently following Lonnberg (1894). Using mitochondrial data, Burbrink (2002, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 25: 465–476) found P. guttatus to comprise three distinct lineages, which were elevated to species level. The name P. guttatus was restricted to populations east of the Mississippi River. The populations in western Louisiana and eastern Texas were named P. slowinskii. Only P. guttatus is found in Virginia.

Description: A stout, moderate-sized snake reaching a maximum total length of 1,829 mm (72.0 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 1,245 mm (49.0 in.) and maximum total length is 1,440 mm (56.7 in.). In the present study, tail length/total length averaged 15.0 ± 1.5% (11.1-17.6, n = 45).

Scutellation: Ventrals 201-229 (ave. = 215.5 ± 5.8, n = 60); subcaudals 52-71 (ave. = 62.3 ± 4.3, n = 54); ventrals + subcaudals 263-291 (ave. = 277.7 ± 6.4, n = 54); dorsal scales weakly keeled or smooth, scale rows at midbody usually 27 (60.4%, n = 53), but may be 23-29 (39.6%); anal plate divided; infralabials 11/11 (62.9%, n = 62) or other combinations of 9-12 (37.1%); supralabials 8/8 (95.2%, n = 62) or other combinations of 7-9 (4.8%); loreal present; preoculars 1/1; postoculars 2/2; temporals usually 2+3/2+3 (71.2%, n = 59) or other combinations of 1-4 (28.8%).

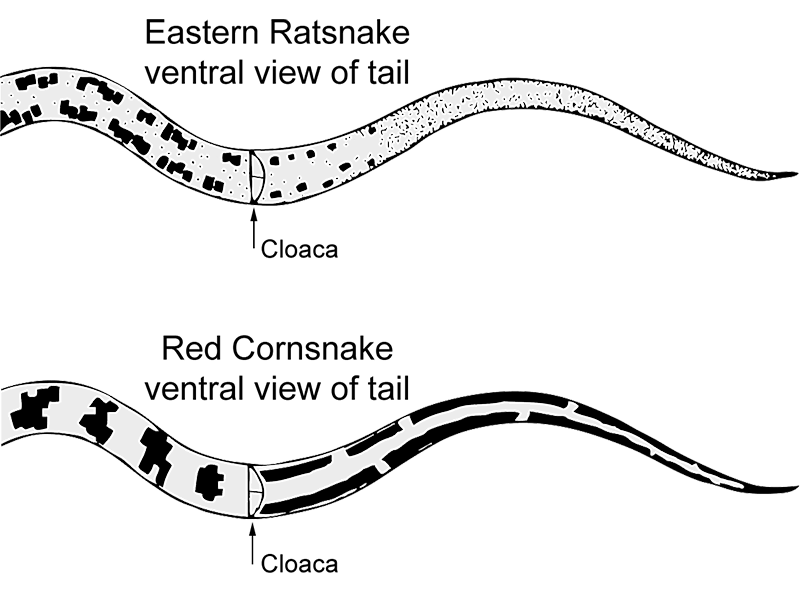

Coloration and Pattern: Series of 27-41 (ave. = 31.8 ± 2.9, n = 56) reddish to chestnut blotches on dorsum of body and 8-14 (ave. = 10.9 ±1.5, n = 33) blotches on tail, each surrounded by black; blotches squarish, except those anteriorly, which are somewhat elongated and have anterior and posterior projections at corners; irregular series of smaller, less-well-defined blotches on sides may be present; background color reddish orange to gray; head and anterior neck possess a pair of longitudinal blotches connected at dorsum of head to form a spear-point pattern with apex anterior to or level with eyes; reddish eye-jaw stripe edged in black continues onto neck; labial scales white and edged in black; venter of body strongly patterned with black-and-white checkerboard design; 2 black stripes on venter of tail. In preservative, reddish colors fade to brown. The firm, muscular body is shaped like a breadloaf in cross section, flat on the venter.

Sexual Dimorphism: Adult male P. guttatus (869.8 ± 155.8 mm SVL, 525-1,245, n = 32) were similar to females (868.0 ± 108.5 mm SVL, 680-1,041, n = 17) in body size, but males reached a longer total length (1,440 mm) than females (1,114 mm). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.002. Average tail length/total length was slightly higher in males (15.2 ± 1.5%, 11.1-17.6, n = 28) than in females (14.5 ± 1.3%, 12.1-16.7, n = 17). Females possessed a higher average number of ventral scales (219.0 ± 6.2, 201-229, n = 21) than males (213.6 ± 4.7, 205-223, n = 39), but fewer average number of subcaudals (females 52-69, ave. = 60.3 ± 4.1, n = 19; males 54-71, ave. = 63.3 ±4.1, n = 35). The number of ventrals + subcaudals (males 263-291, ave. = 276.9 ± 6.2, n = 35; females 266-291, ave. = 279.4 ± 6.5, n = 19) and number of average dorsal body blotches (males 31.8 ± 2.9, 27- 41, n = 38; females 31.9 ± 3.1, 27-37, n = 18) were not sexually dimorphic.

Juveniles: Juveniles are patterned as adults but often have chocolate-brown to dark-chocolate blotches on a gray to reddish-orange body. Hatchlings from Virginia averaged 267.0 ± 29.4 mm SVL (204-291, n = 7) and 296.6 ± 32.7 mm total length (229-335, n = 10), and weighed 7.8-8.3 g (ave. = 7.97 ± 0.19, n = 6).

Confusing Species: This species may be confused with Lampropeltis calligaster and L. triangulum, especially the mountain form of the latter. Both of these species have a short eye-jaw stripe that does not extend beyond the mouth, and neither have anterior blotches with anterior-posterior projections. Corn Snakes are often mistaken for Eastern Copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix), but the latter has hourglass-shaped crossbands and lacks the strong checkerboard pattern on the venter.

Geographic Variation: The background body color is more often gray in P. guttatus from the mountains and upper Piedmont than in those from the eastern Piedmont and Coastal Plain, where it is reddish brown and orange with some gray. Further south, the background color is usually bright orange-red. Geographic variation in scutellation and number of dorsal blotches is not pronounced in Virginia. The average number of ventrals in montane populations (ave. = 215.1 ± 6.6, 205-229, n = 24) was nearly identical to the average number in Piedmont and Coastal Plain populations (ave. = 215.6 ± 5.4, 201-227, n = 35). The number of ventrals + subcaudals (montane ave. = 278.6 ± 6.6, 263-291, n = 21; lowland ave. = 277.2 ± 2.4, 263-291, n = 32) and number of dorsal body blotches (montane ave. = 32.5 ± 3.5, 27-41, n = 23; lowland ave. = 31.5 ± 2.4, 28-37, n = 32) showed similar patterns. Among Coastal Plain populations distributed from New Jersey to the Florida Keys, four characters (ventrals, subcaudals, body blotches, and tail length/total length) exhibited clinal trends of low counts in the north to high counts in the south (Mitchell, 1977). The amount of black ventral pigment and width of black pigment surrounding the dorsal blotches is similar among populations from New Jersey to southern Florida, but less so in populations in the Florida Keys. Only three corn snakes from the Coastal Plain of Virginia were available for that study, but they fit the described trends.

Biology: This is a very secretive snake, infrequently seen even in areas from which it is known. Corn snakes are terrestrial and fossorial, utilizing rodent burrows and tree root canals for shelter and foraging areas. They are associated with open hardwood forests, although they may be occasionally found in pine-dominated agricultural and urban areas. These snakes are often found in fields and open grassy areas where they search for their primary prey, mice. However, these open areas are invariably next to a forested tract. Hoffman (1986) noted that in Alleghany County they have a preference for second growth oak-pine woods in shale hills at elevations <335 m. They are occasionally found around barns and houses where mice and other small mammal prey are abundant. Corn Snakes are occasionally seen crossing roads, especially in the gray hours around sunset. They are most often found in the summer months, although recorded captures are from 4 May through 3 November. Clifford (1976) listed only four P. guttatus (in May and September) in 278 snakes found in a 4-year study in Amelia County. Martin (1976) found that 5 of 545 snakes found in the Blue Ridge Mountains in a 3-year period were Corn Snakes.

Rodents are the preferred prey of this snake, although fledgling birds and lizards are occasionally taken. Uhler et al. (1939) recorded a Five-lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus), a "field" mouse (Peromyscus spp.), and a wood-boring beetle from two specimens. I found a white-footed mouse (P. leucopus) and an unidentified fledgling bird in two specimens. Brown (1979) found meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) and marsh rice rats (Oryzomys palustris) in E. guttata from the Carolinas. Ernst and Barbour (1989b) summarized the known prey of this species. Predators of Corn Snakes have not been recorded for Virginia populations, but Linzey and Clifford (1981) list foxes (Urocyon, Vulpes), bobcats (Felis rufus), opposums (Didelphis virginiana), weasels (Mustek spp.), skunks (Mephitis, Spilogale), and hawks (Buteo spp.).

This species is oviparous and lays one clutch of 7-20 (ave. = 11.3 ± 5.1, n = 6) eggs annually. A clutch of 24 eggs was mentioned in Linzey and Clifford (1981). Tyron (1984) reported that a captive P. guttatus laid two clutches in a single season, but it is unlikely this occurs in nature. Females from South Carolina on high-energy diets produced more and larger eggs than females on poor-quality diets (Seigel and Ford, 1991), suggesting there is considerable variation in annual egg production dependent on prey availability. Mating behavior has been described by MacMahon (1957; also see Ernst and Barbour, 1989b). Copulation in snakes from South Carolina occurred 29 days after emergence from simulated hibernation (Ford and Cobb, 1992). Natural egg-laying sites are unknown. The only known captive mating date in Virginia is 31 May. Mature females I measured were < 680 mm SVL, but Bechtel and Bechtel (1958) found that captive females averaged 635 mm SVL at first mating. Size at maturity for males is unknown. Known egg-laying dates in Virginia are between 18 June and 9 July. Eggs averaged 30-61 x 13-26 mm in size (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b; Seigel and Ford, 1991). Length of incubation was 61-80 days (ave. = 69.5 ± 8.7, n = 4), depending on the temperature of incubation. Known hatching dates are between 22 August and 27 September.

Corn Snakes are seldom seen because they are fossorial. They are solitary animals and have not been found in aggregations. For these reasons the population ecology of this species has not been studied. Corn Snakes are not defensive and will seldom bite.

Remarks: Other common names used in Virginia are spotted coluber (Hay, 1902); brown sedge snake and mole catcher (Dunn, 1915a); scarlet racer and red chicken snake (Carroll, 1950); and red rat snake, pine snake, and chicken snake (Linzey and Clifford, 1981).

Corn Snakes are often killed because many people think they are Eastern Copperheads. Correct identification of Copperheads would help to prevent this loss. Corn Snakes are extremely good at rodent control. Cannibalism has been recorded under captive conditions (Mitchell, 1986).

Conservation and Management: Corn Snakes are highly valued in the pet trade because they are brightly colored, eat mice, and usually do very well in captivity. The number of individuals from Virginia populations lost to the pet trade is unknown. More serious is the loss of habitat due to urban development and fragmentation of habitats. Although not in apparent danger of extirpation in Virginia, Pantherophis guttatus is an important component of Virginia's natural diversity and its status should be monitored.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Craig

Dinwiddie

Essex

Fairfax

Fauquier

Fluvanna

Franklin

Gloucester

Goochland

Greene

Halifax

Hanover

Henry

James City

Lancaster

Louisa

Madison

Montgomery

Nelson

Northumberland

Orange

Page

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince William

Rappahannock

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Scott

Shenandoah

Warren

Westmoreland

CITIES

Richmond

Roanoke

Salem

Verified in 49 counties and 3 cities.

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.