Eastern Gartersnake

Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis

The Official State Snake of Virginia

** Harmless **

Common Name: |

Eastern Gartersnake |

Scientific Name: |

Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Thamnophis is derived from the Greek words thamnos which means "bush" and ophio meaning "snake". |

Species: |

sirtalis is Latin and means "like a garter". |

Subspecies: |

sirtalis is Latin and means "like a garter". |

Vernacular Names: |

Adder, blue spotted snake, broad garter snake, brown snake, Churchhill's garter snake, common streaked snake, common striped snake, dusky garter snake, first and last garden snake, grass garter snake, green spotted garter snake, hooped snake. |

Average Length: |

18 - 26 in. (45.7 - 66 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

43.3 in. (110 cm) |

Record length: |

48.7 in. (123.8 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Coluber sirtalis by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758, based on a specimen sent to him by Pehr Kalm from "Canada." Garman (1892) first used the genus Thamnophis for this species. The history of the scientific name is convoluted. The original Latin description by Linnaeus was discovered by Klauber (1948) to pertain to the Common Ribbonsnake (Thamnophis sauritus), not the Eastern Gartersnake. Klauber substituted the older specific name ordinatus, used by Linnaeus for a presumed Eastern Gartersnake from the Carolinas, for sirtalis. The resulting confusion ended with a decision by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) (see Schmidt and Conant, 1951,1956) to retain the long-used name T. sirtalis for the Eastern Gartersnake and T. sauritus for the Common Ribbonsnake, despite the errors in the older literature (Rossman, 1970; Fitch, 1980). Because Linnaeus's description was incorrect, the ICZN ruled that the official description was to be based on that given by Harlan (1827), which meant that the type locality was, by inference, Pennsylvania (Evans and China, 1966). In the Virginia literature. Cope (1900) used the name Eutaenia sirtalis for this species, following Baird and Girard (1853), and Burch (1940) used the name T. sirtalis ordinatus in reference to specimens with the checkerboard pattern.

Wood and Wilkinson (1952) followed Klauber (1948) and used T. o. ordinatus. Other authors in the Virginia literature have used the current nomenclature. Only the nominate subspecies occurs in Virginia.

Description: A moderate-sized snake reaching a maximum total length of 1,238 mm (48.7 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 898 mm (35.6 inches) and maximum total length is 1,100 mm (43.3 inches). In this study, tail length/total length was 15.4-27.9% (ave. = 22.0 ± 2.2, n = 151).

Scutellation: Ventrals 128-155 (ave. = 142.8 ± 4.4, n = 211); subcaudals 52-81 (ave. = 66.5 ± 6.7, n = 151); ventrals + subcaudals 189-232 (ave. = 209.5 ± 9.8, n = 164); dorsal scales keeled, scale rows 19 at midbody; anal plate single; infralabials 10/10 (68.9%, n = 177) or other combinations of 8-11 (31.1%); supralabials 7/7 (78.9%, n = 185) or other combinations of 6-8 (21.1%); loreal scale present; preoculars 1/1; postoculars 3/3; temporal scales usually 1+2/1+2 (48.6%, n = 177), 1+3/1+3 (24.9%), or other combinations of 1-4 (26.5%).

Coloration and Pattern: Dorsum of body and tail greenish, olive, brown, or black, with a distinct yellow or white middorsal stripe: dorsum may have a pattern of alternating, squarish, black-and- green spots in a checkerboard pattern between stripes or be almost uniformly dark; in some individuals upper and/or lower edges of body scales white; a lateral white to yellow stripe on scale rows 2 and 3 may be present, although less distinct than middorsal stripe, or may be absent in some individuals; color of 1st scale row and lateral margins of ventral scales not as dark as those above scale row 3, the color varying from yellowish-green to gray; venter cream to yellowish green and patternless except for 1 to several small black spots near lateral margins of each ventral scale; dorsum of head greenish, brown, or nearly black; tip of snout brown; in some individuals 2 black blotches project obliquely from parietal scales and are bisected by middorsal stripe; supralabial scales cream-colored and entirely or partially edged in black; chin and infralabials white.

Sexual Dimorphism: Females reached a larger average SVL (515.3 ± 105.0 mm, 395-898, n = 102) than males (408.7 ± 56.4 mm, 338-585, n = 53), and reached a greater maximum total length (1,100 mm; males 728 mm). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.26. Tail length/total length was slightly higher in males (18.3-27.9%, ave. = 23.6 ± 1.8, n = 60) than females (15.4-26.2%, ave. = 20.9 ± 1.7, n = 91). Males had higher average numbers of ventral scales (145.5 ± 4.2, 137-155, n = 73) and subcaudal scales (71.7 ± 5.6, 55-81, n = 62) than females (ventrals 141.4 ± 3.9, 128-154, n = 138; subcaudals 63.3 ± 5.2, 52-79, n = 102). The number of ventrals + subcaudals averaged higher in males (217.4 ± 7.7, 194-232, n = 62) than in females (204.7 ± 7.6, 189-232, n = 102).

Wood and Wilkinson (1952) found that relative tail length and number of subcaudal scales in a litter of neonate T. sirtalis from Newport News were distinctly higher in males. Shine and Crews (1988) demonstrated that females had significantly longer heads than males with the same body size in museum samples from Virginia and other locations

Geographic Variation: Thamnophis sirtalis populations in the lower Coastal Plain had the lowest average counts of ventrals and subcaudals, whereas those in the Appalachian Plateau region had the highest. Accordingly, ventrals varied from 139.4 ± 3.9 (132-152, n = 19) to 146.7 ± 4.7 (141-155, n = 9), subcaudals from 64.0 ± 7.5 (55-77, n = 11) to 71.6 ± 7.8 (58-81, n = 7), and ventrals + subcaudals from 203.9 ± 10.4 (189-225, n = 11) to 217.6 ± 11.1 (200-229, n = 7). Counts for other Virginia populations fell within these values.

Upper-elevation populations (>915 m) of this species often lack lateral stripes, and the middorsal stripe is reduced to a thin line or is faded. The dorsum of these snakes is often darker than those at low elevations.

Biology: Eastern Gartersnakes are terrestrial and can be found in many types of habitats. These include hardwood and pine forests; lowland and upland grasslands and balds; abandoned fields in various stages of succession; along the margins of creeks, rivers, ponds, and lakes; agricultural and urban areas; and freshwater marshes. They are sometimes found in suburban gardens and around barns and houses. Open water is not a requirement, but moist areas are usually present or nearby. Thamnophis sirtalis can be found in every month of the year, but the majority of activity occurs March-November. The earliest recorded observation in Virginia is 16 January (Catesbeiana v43n1) and the latest is 9 December. Body temperatures of snakes in a montane population found under rocks in open fields in June and July averaged 22.8 ± 3.2°C (17.7-29.5, n = 14), with ambient temperatures of 16.0-17.8°C.

In 24 specimens of T. sirtalis from the George Washington National Forest, Uhler et al. (1939) found earthworms (Lumbricus terrestris), millipedes, spiders, various insects, White-spotted Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon cylindraceus), Northern Dusky Salamanders (Desmognathus fuscus), Northern Spring Salamanders (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus), Northern Two-lined Salamanders (Eurycea bislineata), Fowler's Toads (Anaxyrus fowleri), an unidentified snake, and an unidentified small mammal. The following additional prey were in specimens I examined: Pickerel Frogs (Lithobates palustris), Coastal Plains Leopard Frogs (Lithobates sphenocephalus utricularius), and Northern Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon glutinosus). Brown (1979) found several additional prey types in his study in the Carolinas: Marbled Salamanders (Ambystoma opacum), red or mud salamanders (Pseudotriton spp.), Oak Toads (Anaxyrus quercicus), and Cope's Gray Treefrogs (Hyla chrysoscelis). Klemens (1993) reported that an adult from Pulaski County regurgitated a Northern Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus). Linzey and Clifford (1981) speculated that raccoons (Procyon lotor), opossums (Didelphis virginiana), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), weasels (Mustela spp.), hawks (Buteo), owls (Bubo, Strix), Eastern Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula), and Northern Black Racers (Coluber constrictor) preyed on Eastern Gartersnakes. Brooks (1964a) reported a T. sirtalis individual of 395 mm total length in the stomach of a 120 mm (SVL) Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeiana) in Hanover County. Ernst and Barbour (1989b) provided a full list of known predators and prey for this species.

Eastern Gartersnakes are viviparous. Mating occurs in spring soon after emergence from hibernation and in the fall (Fitch, 1970). A single female may be courted by many males at the same time, forming a "mating ball" (Fitch, 1980). The smallest mature male measured was 338 mm SVL and the smallest mature female was 392 mm SVL. The estimated age at maturity for females in Kansas is 2 years (Parker and Plummer, 1987). Recorded birth dates in Virginia are between 22 June and 13 August. Litter size was 9-57 (ave. = 26.2 ± 16.8, n = 22). Wood and Wilkinson (1952) reported a litter size of 48 from a Warwick Co. (= City of Newport News) female born on 30 July.

Thamnophis sirtalis is relatively common wherever snake communities have been studied in Virginia: George Washington National Forest (49 of 889 snakes; Uhler et al., 1939), Amelia County (20 of 278 snakes; Clifford, 1976), and Blue Ridge Parkway and Skyline Drive (35 of 545 snakes; Martin, 1976). Parker and Plummer (1987) tabulated that the estimated densities of Eastern Gartersnake populations in studies in Michigan, Illinois, Kansas, and Canada ranged from 2 to 34 per hectare. A Kansas population experienced a first-year survival rate of 36%, a 50% annual adult survival rate, and an estimated natural longevity of 8 years (Parker and Plummer, 1987).

The Eastern Gartersnake will sometimes flatten its head and anterior body and strike if molested. Juveniles especially will perform this behavior and will strike so forcefully that they may completely leave the ground. Adults will also spray musk from glands located at the base of the tail, and sometimes emit feces in attempts to discourage predators.

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are "first and last" (Dunn, 1918); common garter snake (Hay, 1902; Dunn, 1918,1936; Uhler et. al., 1939; Burch, 1940); spotted garter snake (Burch, 1940); and garden snake, grass snake, and striped snake (Linzey and Clifford, 1981). On March 7, 2016, the Eastern Gartersnake became the Offical State Snake of Virginia - Code of Virginia: CHAPTER 278, § 1-510; State Snake

Conservation and Management: Thamnophis sirtalis is not considered a species of special concern, largely due to its widespread occurrence in Virginia. Its high reproductive rate and its ability to survive in human-disturbed habitats enhances its ability to persist. Populations of T. sirtalis may decline, however, if the primary prey resource, amphibians, also declines and if the habitat is reduced or polluted. This species would be a good candidate for long-term studies designed to obtain information on population dynamics and life history of viviparous snakes. Such information is needed for the development of management plans for species with similar ecologies and life histories that are difficult to study.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Bland

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buchanan

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Carroll

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Clarke

Craig

Cumberland

Dickenson

Dinwiddie

Fairfax

Fauquier

Floyd

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Gloucester

Goochland

Grayson

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Highland

Isle of Wight

James City

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Loudoun

Louisa

Lunenburg

Madison

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Russell

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Sussex

Tazewell

Warren

Washington

Westmoreland

Wise

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Charlottesville

Chesapeake

Danville

Fairfax

Hampton

Hopewell

Lynchburg

Martinsville

Newport News

Norfolk

Radford

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Verified in 87 counties and 15 cities.

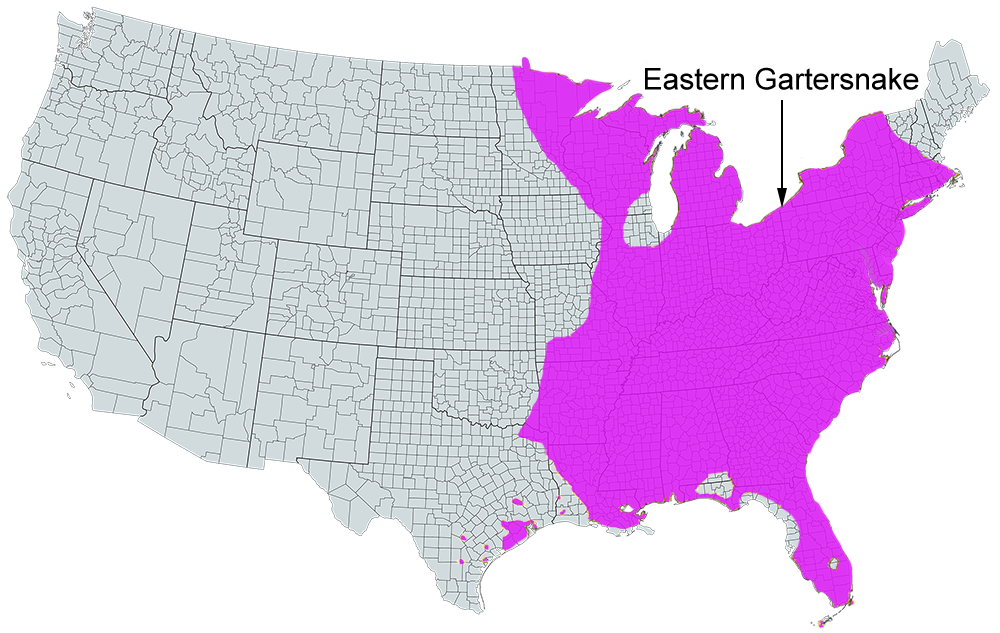

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.