Eastern Hog-nosed Snake

Heterodon platirhinos

** Harmless **

Common Name: |

Eastern Hog-nosed Snake |

Scientific Name: |

Heterodon platirhinos |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Heterodon is derived from the Greek words heteros meaning "different" and odon meaning "tooth". |

Species: |

platirhinos is derived from the Greek words platys meaning "broad or flat" and rhinos meaning "snout". |

Vernacular Names: |

Adder, bastard rattlesnake, black adder, black blowing viper, black hog-nosed snake, black viper snake, blauser, blower, blowing adder, blowing snake, blowing viper, buckwheat-nose snake, calico snake, checkered adder, chuck head, common spreading adder, deaf adder, flat-head, flat-headed adder, hissing snake, hissing viper, mountain moccasin, poison viper, puff adder, red snake, rock adder, sand adder, sand viper, spotted viper, spread-head moccasin, spread-head snake, spread-head viper. |

Average Length: |

20 - 33 in. (51 - 84 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

44.5 in. (113 cm) |

Record length: |

45.5 in. (115.6 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Heterodon platirhinos by Pierre-Andre Latreille (in Sonnini and Latreille, 1801) from a specimen given to him by Palisot de Beauvois. However, no holotype was designated and the type locality was noted only as "North America." Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to the vicinity of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Following Stejneger and Barbour (1917), several Virginia authors used Heterodon contortrix as the scientific name of this species (Dunn, 1918, 1936; Burch, 1940; Hoffman, 1945a; Carroll, 1950; Werler and McCallion, 1951). Klauber (1948) discovered that H. contortrix actually referred to the copperhead and confirmed that Heterodon platyrhinos was the correct name. This combination was used thereafter by many Virginia authors (e.g., Burger, 1958; Conant, 1958, 1975; Mitchell, 1974b; Blem, 1981a) until Platt (1985) corrected the spelling of the specific name. Cope (1900) used the spelling H. platyrhinus. Burch (1940) incorrectly refered to the black phase of this species as Heterodon contortrix niger. No subspecies are recognized.

Description: A stocky, moderate-sized snake reaching a total length of 1,156 mm (45.5 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 955 mm (37.6 inches) and total length is 1,130 mm (44.5 inches). Tail length/total length in Virginia specimens was 12.2-24.0% (average = 18.5 ± 6.1, n = 60).

Scutellation: Ventrals 118-146 (average 130.5 ± 6.2, n = 98); subcaudals 37-64 (average 48.5 ± 4.5, n = 92); ventrals + subcaudals 163-200 (average = 178.5 ± 6.0, n = 91); dorsal scales keeled, scale rows usually 25 (76.3%, n = 59) at midbody, but may be 21- 24 (23.7%); anal plate divided; infralabials 10/10 (35.9%, n = 64) or combinations of 9-11 (60.9%) or 10-12 (3.1%); supralabials 8/8 (88.5%, n = 61) or other combinations of 7-9 (11.5%); rostral scale upturned with a posterior keel; single azygous scale present separating nasal scales; loreal present; no preocular or postocular scales; ocular ring scales 10/10 (29.4%, n = 34) or other combinations of 8-12 (70.6%); temporals usually 3+4/3+4 (57.7%, n = 52) or other combinations of 2-5 (42.3%).

Coloration and Pattern: Two color phases are common in Virginia: (1) a patterned phase (79.6%, n = 98), characterized by a series of 19-27 (average = 23.2 ± 2.4, n = 12) black or dark-brown blotches along middorsal line, with alternating black spots on sides; body color consists of varying combinations of gray, tan, pink, yellow, orange, and red; venter of body and tail immaculate cream to dark gray; in some snakes, anterior portion of venter cream but black to gray pigment increases in concentration posteriorly; tail may be light in color while rest of venter dark; chin and supralabials white; a black stripe between eye and posterior margin of mouth occurs on some individuals; black crossbar lies in front of eyes; 2 dark, broad patches on side of neck; and (2) a melanistic phase (20.4%, n = 98), characterized by uniformly black coloration dorsally, usually without evidence of a pattern; venter of body and tail on these snakes may be cream peppered with black or all dark gray; in some, venter of tail is cream and venter of body is dark gray; some melanistic individuals are grayish with varying degrees of dark blotch pattern. The posterior tooth on each of the maxillary bones is enlarged.

Sexual Dimorphism: Sexual dimorphism is expressed in scutellation, body proportions, and number of dorsal blotches. Average adult SVL in males was less (518.8 ± 119.1, 315-880, n = 34) than in adult females (644.5 ± 118.9, 523-955, n = 20). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.24. Males had proportionally longer tails (tail length/total length 14.8-24.0%, average = 19.3 ± 6.9, n = 37) than females (12.2-21.0%, average = 15.4 ± 2.1, n = 22). Males had fewer average number of ventrals (average = 127.3 ± 4.7, 118-141, n = 61) but more subcaudal scales (average = 50.1 ± 3.9,41-60, n = 59) than females (ventrals average = 136.2 ± 4.0, 126- 146, n = 34; subcaudals average = 45.8 ± 5.0,37-64, n = 30). Average number of ventrals + subcaudals (males 177.2 ± 5.6,163-190, n = 59; females 181.6 ± 6.0, 172-200, n = 29) and average number of dorsal body blotches (males 22.8 ± 2.5,19-27, n = 12; females 22.9 ± 2.5, 20-25, n = 8) were similar between sexes. Scott (1986) found that female H. platirhinos (n = 28) from the Virginia portion of Assateague Island were significantly longer (males 442 ± 18 mm SVL, females 544 ± 27 mm SVL), heavier (males 94.9 ± 9.6 g, females 140.6 ± 14.5 g), and had more dorsal blotches (males 21.8 ± 0.3, females 23.7 ± 0.4) than males (n = 38). Mainland Virginia females were heavier (average = 198.5 ± 133.5 g, 72- 429, n = 6) than males (average = 113.0 ± 40.4 g, 60- 170, n = 6).

Juveniles: All juveniles examined (n = 23) exhibited blotch patterns similar to those found in adults, except that a pinkish coloration was more prominent. Hatchling H. platirhinos are chunky with a prominent upturned rostral scale. Hatchling size in Virginia is unknown. Ernst and Barbour (1989b) noted that they were 168-250 mm in total length.

Confusing Species: This species is usually not confused with any other snake because of its behavior when found in the field (see below). No other Virginia species possesses the upturned rostral scale or exhibits similar antipredator behaviors. Eastern Copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix) have a series of brown, hourglass-shaped crossbands on the dorsum.

Geographic Variation: There is no geographic variation in number of blotches or counts of scale characters among physiographic regions in Virginia that cannot be explained by the small regional sample sizes. Edgren (1961) found that the geographic pattern in number of dorsal blotches is from high counts in the north to low counts in the south. Average counts for his eastern Virginia samples (males 24, females 24) averaged lower than those from New England (males 25-28, females 28-29) but higher than those from the Carolinas (males 21-22, females 22-24). The pattern for ventrals was more complex, with relatively higher average counts in the mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain (males 124-128, females 138-139) compared with lower counts in Florida (males 122-128, females 134-136) and New England (males 122-123, females 133-134).

Biology: Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes inhabit areas with sandy soils. They have been found in fields; open grassy areas adjacent to woods; and in open pine, mixed pine and deciduous hardwood, and pure hardwood forests. They are seldom encountered in densely wooded tracts, but are more frequently found in ecotonal areas. Populations of unknown sizes inhabit agricultural and urban areas with patches of appropriate habitat. Wet areas are avoided. They are completely terrestrial but will enter water to migrate between areas. Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes are diurnal, are seldom found under surface objects, and burrow into the sandy soil at night and for winter hibernation. On 26 January 1945, N. D. Richmond (pers. comm.) found a juvenile 15 cm beneath the soil surface, the top 7-8 cm of which was frozen. Burrowing is accomplished by the head thrusting downward from a bent position, using side-to-side motions and force from the anterior body (Davis, 1946). Museum records indicate an activity period of 1 March-6 December, although most records are in April through early October. Body temperatures of active Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes averaged 29.0 ± 4.3°C (23.4- 32.6, n = 4), with ambient temperatures of 19.2- 26.6°C (average = 23.6 ± 3.9).

Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes are almost exclusively predators of toads, although other prey types are occasionally taken. The following have been recorded from Virginia snakes: American Toads (Anaxyrus americanus), Fowler's Toads (Anaxyrus fowleri), Southern Toads (Anaxyrus terrestris), Eastern Spadefoots (Scaphiopus holbrookii), true frogs (Lithobates spp.), Red-spotted Newts (Notophthalmus viridescens), plethodontid salamanders (Plethodon spp.), an unidentified mouse, and chipmunks (Tamias striatus) (Uhler et al., 1939; J. C. Mitchell, pers. obs.). Ernst and Laemmerzahl (1989) reported the consumption of a Spotted Salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) by an adult male in Fairfax County. The toxins found in the skin glands of toads are neutralized by enzymes in the digestive tracts of H. platyrhinos. Prey are swallowed alive, and live toads are sometimes regurgitated. Platt (1969) recorded a number of snakes and predatory birds as predators of Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes. No predators of Virginia snakes have been recorded.

Eastern Hog-nosed Snakes are docile animals that bluff and feign death to discourage potential predation against them. At the initial encounter, the snake will inflate its body and neck, coil with head elevated and often turned sideways, hiss by rapidly expelling air from the lungs, and strike with mouth open or closed. They will not bite. If this does not deter the predator and if the snake is touched, it will writhe as if in pain and agony, turn over repeatedly, open the mouth, extrude the tongue, and evert the cloaca. The mouth and cloaca often accumulate dirt or sand. After a minute or so of this behavior, the snake will lie on its back and become completely limp, as if dead. It will remain limp if it is picked up, but will roll over on its back if placed on its venter, as though all good dead snakes have to lie on their backs. If left unmolested for a few minutes, the snake will look to see if the predator is still around, and if the coast is clear, turn over and crawl away. The bluffing behavior has awarded it a plethora of vernacular names (see "Remarks").

In Virginia, H. platirhinos females laid 17-35 eggs (average =29.3±8.3, n = 4 clutches) in sandy soil in July. The smallest mature female I measured was 457 mm SVL and the smallest male was 350 mm SVL. Spring mating has been documented (Wright and Wright, 1957) but fall mating has not. Egg-laying dates of 13 and 15 July have been recorded for Virginia snakes but 27 May-28 August elsewhere in its range (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b). Eggs averaged 21-39 x 13-28.5 mm in size, and incubation time was 50-65 days (Platt, 1969). Hatching occurs in August and September. Known hatching dates in Virginia are 23-27 August (Dunn, 1915d) and 15-18 September.

This is an abundant snake in some areas but the density depends on the amount of suitable habitat and number of prey available. Scott (1986) estimated a population density of 4.8 snakes per hectare on southern Assateague Island. Clifford (1976) found that this species was the third most abundant snake in Amelia County (24 of 278 in a 4-year period). However, Martin (1976) recorded only 17 H. platirhinos among the 545 snakes found in the Blue Ridge Mountains in a 3-year period. On Assateague Island, the sex ratio was 1:1, distance moved between captures was 40-760 m (average = 390), juvenile growth was 2.2 cm per month, and growth of an adult male was 1.0 cm per month (Scott, 1986).

Remarks: Other common names in the Virginia literature are black adder, blowing viper and spreading adder (Hay, 1902); spreadhead moccasin and puff-adder (Dunn, 1915a; Burch, 1940); spreadhead (Dunn, 1936; Carroll, 1950); puff viper, possum snake, hissing adder, and puff head (Linzey and Clifford, 1981); and bull adder.

An instance of an accidental bite by this species reported by Grogan (1974) resulted in mild envenomation to the victim while he was handling the snake. The Eastern Hog-nosed Snake was feigning death. The writhing snake, with its mouth open, caught its teeth on the victim's arm. The symptoms were swelling, pain similar to a strong bee sting, dark purple discoloration around the wound changing to redness, and nausea. Although H. platirhinos is not considered venomous, the saliva is apparently toxic to some people. Caution should be exercised when handling this snake. One albino juvenile H. platirhinos has been reported from Fairfax County (Anonymous, 1961).

Conservation and Management:This is a Tier IV Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Virginia’s Wildlife Action Plan. There is concern about the decline of toad populations in Virginia over the past several decades. If this is a real trend, perhaps associated with pesticide and herbicide application and the increase in numbers of vehicles on Virginia's roads (Hoffman, 1992), then H. platirhinos populations would also be expected to decline. Any effort to conserve this unique element of Virginia's biodiversity should include the preservation of sandy habitats in wooded areas.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Botetourt

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Clarke

Craig

Culpeper

Cumberland

Dickenson

Dinwiddie

Fairfax

Fauquier

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Gloucester

Goochland

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Highland

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Loudoun

Louisa

Lunenburg

Madison

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Tazewell

Warren

Washington

Westmoreland

Wise

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Charlottesville

Chesapeake

Hampton

Newport News

Norfolk

Petersburg

Portsmouth

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Verified in 84 counties and 11 cities.

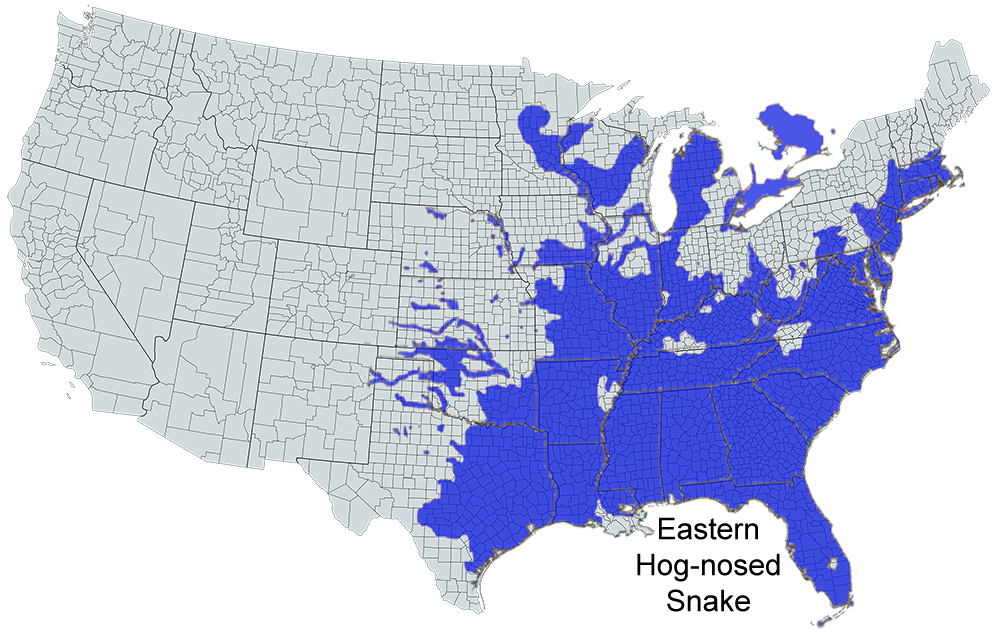

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.

0010_small.jpg)

0009_small.jpg)

0008_small.jpg)

0006_small.jpg)