Northern Black Racer

Coluber constrictor constrictor

** Harmless **

Common Name: |

Northern Black Racer |

Scientific Name: |

Coluber constrictor constrictor |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Coluber is Latin for "snake". |

Species: |

constrictor is derived from the Latin words con which means "together" or "with" and strictus which means "drawn together" or "tight". |

Subspecies: |

constrictor is derived from the Latin words con which means "together" or "with" and strictus which means "drawn together" or "tight". |

Vernacular Names: |

American black snake, American racer snake, black chaser, black runner, blue racer, chicken snake, cow sucker, green snake, hoop snake, horse racer, slick black snake, true black snake, white-throated racer. |

Average Length: |

36 - 60 in. (90 - 152 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

70.7 in. (179.5 cm) |

Record length: |

73 in. (185.4 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Coluber constrictor by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758. Linnaeus designated no holotype, but listed the type locality as "America septentrionale." The type locality was later restricted to "Canada" by Schmidt (1953). Dunn and Wood (1939) suggested that Philadelphia was the type locality. Two subspecies are currently recognized: the Northern Black Racer (Coluber constrictor constrictor) (Linnaeus) and the Southern Black Racer (Coluber constrictor priapus). Only the nominate subspecies occurs in Virginia. The following synonyms have been used in the early Virginia literature: Bascanion constrictor (Drowne, 1900; Hay, 1902; Dunn, 1915d) following Baird and Girard (1853) and Zamenis constrictor (Cope, 1900) following Boulenger (1893-1896). All other Virginia authors have used the current nomenclature.

Description: A long, shiny, black snake reaching a maximum total length of 1,854 mm (73.0 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 1,395 mm (54.9 in.) and total length is 1,795 mm (70.7 in.). Tail length/total length in Virginia specimens averaged 23.3 ± 2.1% (15.3-29.1, n = 143).

Scutellation: Ventrals 131-189 (ave. = 179.1 ± 5.3, n = 183); subcaudals 63-108 (ave. = 92.1 ± 7.3, n = 147); ventrals + subcaudals 222-289 (ave. = 276 ± 9.6, n = 147); dorsal scales smooth, scale rows usually 17 (90.7%, n = 184) at midbody, but may be 15-16 (8.3%); anal plate divided; infralabials 8/8 (35.7%, n = 112) or 9/9 (26.8%) or other combinations of 7-10 (37.5%); supralabials usually 7/7 (75.8%, n = 128) or other combinations of 6-8 (24.2%); loreal present; preoculars 2/2; postoculars 2/2; temporals usually 2+2/2+2 (74.8%, n = 131) or other combinations of 1-3 (25.2%).

Coloration and Pattern: Body of adults slender and uniformly black dorsally, dark gray ventrally; venter of tail uniformly light gray; head black except for anterior portion of snout, which is brownish; chin and a variable portion of venter of neck white; some white pigment on supralabial scales in some individuals; racers in shedding cycle appear dark gray to light brown.

Sexual Dimorphism: Northern Black Racers show little sexual dimorphism. Average adult female SVL (1,020.0 ± 150.4 mm, 750-1,360, n = 82) was similar to average adult male SVL (1,036.1 ± 173.5 mm, 631-1,395, n = 78). Sexual dimorphism index was -0.02. Both exhibited an identical average tail length/total length (males 23.2 ± 2.0%, 15.3-26.9, n = 61; females 23.2 ± 1.9%, 19.2-29.1, n = 66). Body mass in adult males was similar (ave. = 351.2 ± 150.5 g, 114-685, n = 25) to that in adult females (ave. = 349.6 ± 146.1, 140-613, n = 24). Males possessed a similar number of ventral scales (ave. = 178.8 ± 3.5,171-188, n = 77) as females (ave. = 180.1 ± 3.7,169-187, n = 82), as well as ventral + subcaudal scales (males 271.2 ± 9.4,242-289, n = 61; females 270.6 ± 7.4,249-284, n = 64).

Juveniles: Upon hatching, juveniles have a dorsal pattern of dark-gray to reddish-brown blotches (ave. = 59.4 ± 5.1, 53-75, n = 32) on a light-gray to brown body. The venter is cream in color and may be plain or bear an irregular series of black dots. Small black or brown dots often occur laterally on the dorsum. The chin is plain white and the head is mostly brown, interspersed with varying amounts of gray. The venter of the tail is plain white. The juvenile pattern becomes occluded with age, the melanin becoming so abundant that all but the light chin and brown snout are obscured. This pattern is lost by about age 3 and at a SVL of about 300 mm. Virginia hatchlings averaged 224.7 ± 8.4 mm SVL (206- 235, n = 28), 298.3 ±11.4 mm total length (275- 315), and 6.3 g (ave. for one litter) body mass.

Confusing Species: Adults of this species are often confused with adult specimens of Pantherophis alleghaniensis; however, the latter has a breadloaf-shaped body in cross section, keeled scales middorsally, and varying amounts of white on the flat venter. Juveniles of Pantherophis alleghaniensis have an eye-jaw stripe, a checkerboard pattern on the venter, and (usually) irregular blotches with anterior and posterior projections on the corners. Black-phase individuals of Heterodon platirhinos are short and stocky compared to C. constrictor, and they have a broader head with an upturned snout.

Geographic Variation: Little geographic variation is exhibited by C. constrictor in Virginia. Maximum body size, proportions, and color are similar across physiographic regions. There was a trend toward fewer average ventral scales west of the Blue Ridge Mountains (ave. = 173.8 ± 14.0, 131-185, n = 12) compared with populations in and east of these mountains (ave. = 179.5 ± 3.9, 162-189, n = 165). This trend also occurred in ventrals + subcaudals (mountains 262.3 ± 16.5, 222-276, n = 10; east 271.7 ± 8.7, 242-289, n = 131). Other scutellation characters exhibited similar ranges of variation across regions. Auffenberg (1955) determined that the number of ventral scales varied clinally in eastern North America from low counts in Maine (about 170) to high counts from New York (180) to southern Florida (183). The number of subcaudals exhibited a similar cline (about 95 in the north to 105 in southern Florida). Ventral scale counts for Virginia populations east of the mountains fit this pattern. However, subcaudal scale counts were slightly lower than expected from Auffenberg's results.

Biology: Northern Black Racer are terrestrial and are found in open, grassy areas or in open forest adjacent to grassy areas. The habitat is usually dry (xeric). Northern Black Racers inhabit agricultural and urban areas, as well as barrier islands and grasslands in the mountains. This species is often seen crossing roads during the day, where many are killed. Because it is diurnal. Coluber constrictor seeks refuge under surface objects, such as logs, discarded boards and car hoods, and other debris during the night and on cool days during the normal activity season (April-September). Extreme records are 22 March (adult) and 30 November (juvenile). One adult male was found DOR in Fairfax in January (no specific date; C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). Body temperatures of active snakes were 26.1-38.0°C (ave. = 31.9 ± 4.7, n = 5), and inactive snakes under boards and tin were 19.0-35.6°C (ave. = 30.4 ± 5.8, n = 9).

Coluber constrictor has a catholic diet. The following prey have been recorded for Virginia snakes: larvae of butterflies and moths, adult noctuid moths, June bugs, cicada nymphs, Dusky Salamanders (Desmognathus fuscus), frogs (Lithobates spp.), Spring Peepers (Pseudacris crucifer), Eastern Fence Lizards (Sceloporus undulatus), skinks (Plestiodon spp.), Northern Watersnakes (Nerodia sipedon), Eastern Wormsnakes (Carphophis amoenus), ring-necked snakes (Diadophis punctatus), Smooth Greensnake (Opheodrys vernalis), Eastern Gartersnakes (Thamnophis sirtalis), red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), white-eyed vireos (Vireo griseus), warblers, sparrows, bird eggs, chipmunks (Tamias striatus), common moles (Scalopus aquaticus), short-tailed shrews (Blarina spp.), unidentified shrews (Sorex spp.), white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus), and southern flying squirrels (Glaucomys volans) (Richmond and Goin, 1938; Uhler et al., 1939; Hoffman, 1945a; C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.; J. C. Mitchell, pers. obs.). Invertebrates are most often found in juveniles, and rodents and reptiles are primary prey of adults. A host of other prey are listed for this species by Fitch (1963a) and Ernst and Barbour (1989b).

Coluber constrictor does not constrict, as the scientific name implies, but pins its prey with body loops and swallows it alive. Madison (1978) determined that Northern Black Racers in Warren County selectively preyed on lactating female meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) and the largest males in the population. He surmised that voles that defended their territory or litters were more susceptible to predation. Cannibalism of a conspecific by a Surry County adult was reported by deRageot (1964). Free-ranging domestic cats prey on C. constrictor in Virginia (Mitchell and Beck, 1992). Ernst and Barbour (1989b) summarized the known predators for this species.

Northern Black Racers from Virginia laid 12-36 eggs (ave. = 21.0 ± 8.3, n = 14 clutches) in and under logs; under mattresses, rocks, sheet metal, and other objects; and in rodent tunnels and mulch and sawdust piles. Ten clutches from Fairfax County contained 13-22 eggs (ave. = 18.5) (C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). Mating has been observed on 28 May in Frederick County (W. H. Martin, pers. comm.), 10 April and 3 and 7 May in Fairfax County (C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.), and on 8 June in the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge (D. Schwab, pers. comm.). The smallest mature female I measured was 713 mm SVL; the smallest adult male was 546 mm SVL. Known egg-laying dates are between 24 May and 26 June. Werler and McCallion (1951) noted an egg-laying date of 27 June. Eggs averaged 29.5 ± 3.2 X 20.5 ± 1.7 mm (length 25.0-41.5, width 15.7-23.5, n = 112) in size and weighed an average of 7.2 ± 0.7 g (5.8- 8.5, n = 62). Length of incubation in the laboratory was 54-68 days, and hatching occurred from 2 August to 6 September.

Martin (1976) recorded 25 specimens of C. constrictor out of 545 snakes observed on the Blue Ridge Parkway and Skyline Drive over a 3-year period, and Clifford (1976) listed 29 Northern Black Racers out of 278 snakes he recorded in Amelia County over a 4-year period. The population ecology of Coluber constrictor has not been studied in Virginia. Densities of one to three adults per hectare in Mason Neck National Wildlife Refuge were estimated by C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.). Fitch (1963a) found a density of three to seven per hectare in Kansas, an adult survivorship rate of 62%, and a natural life expectancy of 10 years.

Northern Black Racers are active, diurnal predators that use vision to search for prey. Coluber constrictor actively forages with the forepart of the body raised off the ground and the head held horizontally searching for prey. They will seek escape by swiftly moving to thick grass cover or into a burrow entrance. When caught, racers will bite repeatedly, although the bite is similar to a briar scratch. Because they are active snakes that widely search for prey, they have large home ranges. Movements of up to 1.6 km have been recorded (Fitch, 1963a). Although black racers are usually solitary animals, large numbers of them may overwinter in a favorable hibernaculum (Conant, 1938). Northern Black Racers have been found to overwinter with Eastern Copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix) in Fairfax County (C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.).

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are black snake and racer (Conant, 1945; Carroll, 1950); hoop snake, slick blacksnake, cow sucker, and horse racer (Dunn, 1915a, 1936); black-snake and blue racer (Hay, 1902); and horse runner and horse whipper (Brothers, 1992).

Beck (1952) recounts a myth from the Rappahannock County area that may pertain to this species because it is commonly believed they chase people. In reality they are just willing to pass by a potential threat if there is an escape route. The hoop snake carries its sting on its tail and sometimes puts it in its mouth, rolls in pursuit of people, and stings trees (especially beeches, Fagus spp.) out of spite, which instantly wither and die. Versions of this story also pertain to the Eastern Mudsnake (Farancia abacura), which does not occur in Rappahannock County.

Conservation and Management: Because this species can move long distances, occupy habitats associated with open grassy areas, and eat a wide variety of prey, it is found throughout most of Virginia. Despite the fact that many are killed each year on roads by vehicles and farm machinery, C. constrictor appears to be secure in the state. Maintenance of black racers in local areas requires open fields and woodlands.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Bland

Botetourt

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Clarke

Craig

Culpeper

Cumberland

Dinwiddie

Fairfax

Fauquier

Floyd

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Gloucester

Goochland

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Highland

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Loudoun

Louisa

Lunenburg

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Russell

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Warren

Westmoreland

Wise

Wythe

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Chesapeake

Danville

Fredericksburg

Hampton

Martinsville

Newport News

Norfolk

Petersburg

Poquoson

Portsmouth

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Williamsburg

Winchester

Verified in 85 counties and 16 cities.

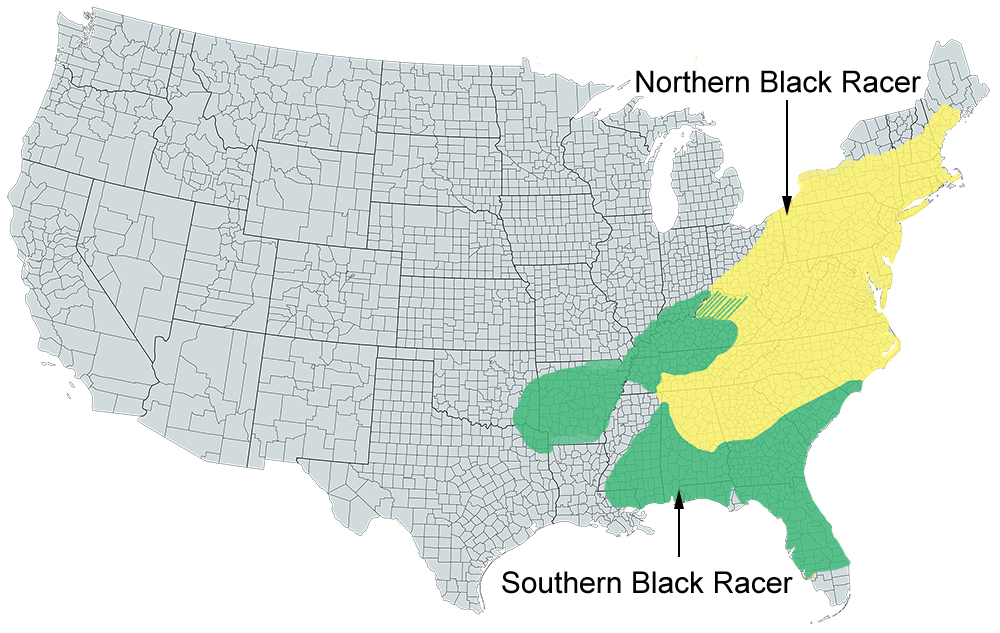

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.

026_small.jpg)