Red-bellied Snake

Storeria occipitomaculata

** Harmless **

Common Name: |

Red-bellied Snake |

Scientific Name: |

Storeria occipitomaculata |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Storeria is in honor of David Humphreys Storer, an 18th-century, zoologist from New England. |

Species: |

occipitomaculata is derived from the Latin words occiput which means "the back part of the head" and macula meaning "spot". |

Vernacular Names: |

Brown snake, copper snake, ground snake, little brown snake, little red-bellied snake, red-billed brown snake, red-bellied garter snake, red-bellied ground snake, spot-neck snake. |

Average Length: |

8 - 10 in. (20.3 - 25.4 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

15 in. (38.1 cm) |

Record length: |

16 in. (40.6 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Coluber occipito-maculatus by David Humphreys Storer in 1839, based on a specimen from Amherst, Massachusetts. Baird and Girard (1853) first placed this species in the genus Storeria. Several earlier authors (e.g., Dunn, 1936; Trapido, 1944) followed the original description and hyphenated the specific name. Others (e.g.. Cope, 1900; Dunn, 1918) eliminated the hyphen. Except for this variation, the name has been stable since 1853. Stejneger and Barbour (1917) and Smith and Huheey (1960a) determined that the original description of Coluber leberis linnaeus, 1758, used by Baird and Girard (1853) for the Queensnake (Regina septemvittata), was actually that of a Storeria occipitomaculata. By the Law of Priority, C. leberis should have been the scientific name of the Red-bellied Snake. However, because S. occipitomaculata had been stable since its description by Baird and Girard, Smith and Huheey (1960b) petitioned the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to officially suppress Coluber leberis and add the name S. occipitomaculata to the Official List of Species Names in Zoology.

Description: A small snake reaching a maximum total length of 406 mm (16.0 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 295 mm (11.6 inches) and maximum total length is 381 mm (15.0 inches). In this study, tail length/total length was 11.8-26.3%

Scutellation: Ventrals 100-134 (ave. = 119.0 ± 6.1, n = 43); subcaudals 37-54 (ave. = 43.5 ± 4.3, n = 42); ventrals + subcaudals 149-185 (ave. = 162.4 ± 7.4, n = 42); dorsal scales keeled, scale rows 15 at midbody; anal plate divided; infralabials 7/7 (75.0%, n = 40) or combinations of 5-8 (25.0%); supralabials 6/6 (80.0%, n = 40) or combinations of 5-7 (20.0%); loreal scale absent; preoculars 2/2; postoculars 2/2; temporal scales usually 1+2/1+2 (86.8%, n = 38) or combinations of 1-3 (13.2%).

Coloration and Pattern: Dorsum of body and tail light brown, dark gray, or black with some indication of 2 or 4 thin black stripes; body scales contain varying amounts of black flecking-the amount of black determines amount of brown visible; dark-gray specimens have gray scales with abundant black flecking; black flecking on these snakes may be concentrated in lateral and dorsal areas where it forms thin stripes; a middorsal stripe of tan to black outlined by narrow, dark stripes on scale row 7 on each side; scales on row 2 may be edged white-these appear as stripes or small white spots; venter immaculate red, rarely yellowish; dark-gray pigmentation occupies 20-25% of venter on each side forming what may appear as 2 dark stripes along lateral margins of venter, in these individuals red color reduced to a narrow stripe along midventral line about one-half to three-fourths the width of ventral scales; anterior portion of venter whitish; dorsum of head brown to gray to black, although anteriormost portions brown; 3 cream to orange spots on neck, 1 mid-dorsally and 1 on each side; in some individuals these spots may be connected by a line of similar color; supralabials, except the 5th, which is white bordered by black on lower edge, may be colored as rest of head; chin and infralabials cream and speckled in black; some specimens nearly all black, although 3 spots on neck and white edges of dorsal scales present.

Sexual Dimorphism: Sexual dimorphism is expressed in body size and scutellation. Females reached a larger average SVL (201.8 ± 43.7 mm, 152-295, n = 26) than males (180.2 ± 35.8 mm, 155-252, n = 6) and a larger total length (381 mm; males 320 mm). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.12. Average tail length relative to total length was slightly higher in males (23.3 ± 2.5%, 18.8- 26.3, n = 10) than females (20.1 ± 2.5%, 11.8- 24.7, n = 29).

Females had a higher average number of ventral scales (120.2 ± 5.4, 111-134, n = 31) than males (116.2 ± 7.2, 100-131, n = 12), but a smaller average number of subcaudals (females 42.0 ± 3.1, 37-49, n = 30; males 47.3 ± 4.8, 38-54, n = 12). The number of ventrals + subcaudals was similar between sexes (males 163.4 ± 8.7, 152-185, n = 12; females 162.1 ± 7.0, 149-175, n = 30).

Juveniles: Juveniles are uniformly black when born except for the 3 cream to yellow spots on the neck. Neonate S. occipitomaculata were 58-66 mm SVL (ave. = 61.0 ± 2.3, n = 9) and 70-84 mm total length (ave. = 77.8 ± 4.2). Neonatal birth weight is unknown.

Confusing Species: This species may be confused with several other small snakes. The congeneric S. dekayi has a row of paired dorsal spots and lacks the 3 spots on the neck and red venter. See the S. dekayi account for other confusing species.

Geographic Variation: Small sample sizes from most regions preclude analysis of regional geographic variation in scutellation by sex. The number of ventrals + subcaudals varied from 158.3 ± 4.9 (152-167, n = 12) in the upper Piedmont to 162.6 ± 11.0 (149-185, n = 9) in the upper Coastal Plain and 165.3 ± 5.5 (157-175, n = 12) in the Ridge and Valley north of the New River. These values compare well with those reported in Trapido (1944) for his Atlantic Coast sample. Average values for ventrals and subcaudals for males and females (see "Sexual Dimorphism") differed by similar degrees with that found for North Carolina samples (Rossman and Erwin, 1980). Geographic variation among subspecies is based on variation in the patterns on the neck and 5th labial scale (Conant and Collins, 1991). Body sizes of adult males and females from Virginia (see "Sexual Dimorphism") more closely resemble the large snakes from a Michigan population studied by Blanchard (1937) than the smaller snakes from a South Carolina population studied by Semlitsch and Moran (1984).

Biology: Red-bellied Snakes are secretive, terrestrial snakes found in open hardwood forests, mixed hardwood-pine forests, old fields with grass and shrub communities, pine forests, and in woodlots in agricultural and urban areas, as well as along the edges of freshwater wetlands. Although they are primarily nocturnal, they can be found under all manner of surface objects, such as rocks, logs, boards, debris, bark, and leaves. They are not habitat specialists, as they have been found in moist and xeric areas. The period of seasonal activity in Virginia is 18 March to 19 October (based on museum records), although individuals may be found in all months of the year. In South Carolina, Semlitsch and Moran (1984) determined that S. occipitomaculata moved to moist areas following seasonal drying of the soil. These snakes overwinter in anthills, unused rodent burrows, and soil containing crevices and passageways (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b). Storeria occipitomaculata is a predator of slugs. Semlitsch and Moran (1984) found 100% slugs (families Limacidae and Philomycidae) in 10 South Carolina Red-bellied Snakes. They will occasionally eat other prey, such as insects, earthworms, millipedes, and sowbugs (isopods) (Wright and Wright, 1957). Known predators are largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), domestic chickens, Eastern Milksnakes (Lampropeltis triangulum), Eastern Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula), and Northern Black Racers (Coluber constrictor) (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b). Linzey and Clifford (1981) noted that an adult Marbled Salamander (Ambystoma opacum) killed and ate a small Red-bellied Snake in captivity.

Females of this species are viviparous. Mating occurs in the spring and fall (Martof et al., 1980). Spermatozoa remain viable over winter in oviducts of the female and can be used for spring fertilization (Fitch, 1970). The smallest mature male from Virginia was 137 mm SVL and the smallest mature female was 151 mm SVL. In South Carolina, the smallest male was 118 mm SVL and the smallest female was 126 mm (Semlitsch and Moran, 1984). These authors also found that age at maturity was about 2 years. Known birth dates in Virginia are 23 July and 3 and 7 August. Full-term embryos were found in specimens on 3 and 25 June and on 4 July. Litter sizes were 2-12 (ave. = 7.5 ±2.8, n = 10). This was lower than averages of 9.0 in South Carolina (Semlitsch and Moran, 1984), 9.2 in Michigan (Blanchard, 1937), and 9.4 from throughout the range (Fitch, 1970).

This snake appears to be more abundant in the mountains and Piedmont (16 specimens each) than in the Coastal Plain (11 specimens). Clifford (1976) found 4 S. occipitomaculata specimens out of 278 snakes recorded in Amelia County over a 4-year period. However, neither Uhler et al. (1939) nor Martin (1976) found a single specimen in their extensive surveys in the Virginia mountains. In studies in Michigan and South Carolina, recapture rates of marked S. occipitomaculata were very low (<13%) (Blanchard, 1937; Semlitsch and Moran, 1984). These authors speculated that there may be a rapid turnover of individuals in the population, that the snakes were abundant, or that they moved out of the area. The first hypothesis is supported by the observation that these snakes are short-lived in captivity (2 years; Snider and Bowler, 1992) and by the data suggesting high juvenile production and recruitment into the population (Semlitsch and Moran, 1984).

This snake will not bite when handled, but may emit musk from glands at the base of the tail, curl the upper lips exposing the black mouth, and even play dead.

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are redbellied ground snake (Dunn, 1936), and worm snake and spot-necked snake (Linzey and Clifford, 1981). Verification of the distribution of this species in southwestern Virginia, on the Eastern Shore, and in numerous counties is needed for a full delineation of its range in Virginia. C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) witnessed the extinction of a local population of S. occipitomaculata in a boggy area in Fairfax County. An urban development project destroyed the habitat.

Conservation and Management: The dynamic nature of populations (e.g., turnover, movements in the habitat) suggests that Storeria occipitomaculata is sensitive to local perturbations, especially habitat drying. The relationship of population size to size of habitat fragments, as well as how the habitat drying cycle affects movement patterns, needs to be determined. Habitat drying may increase after forest fragmentation and may have potentially harmful consequences for these snakes and their prey. This may be especially true in small fragments, if moist areas are eliminated. Maintenance of forest litter and cover objects in forested areas with year-round moisture will help ensure the presence of this species.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Appomattox

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Bland

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Craig

Culpeper

Cumberland

Fairfax

Fauquier

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Goochland

Greene

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Highland

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Louisa

Madison

Mecklenburg

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Rappahannock

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Scott

Shenandoah

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Westmoreland

York

CITIES

Chesapeake

Danville

Manassas

Petersburg

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Verified in 66 counties and 6 cities.

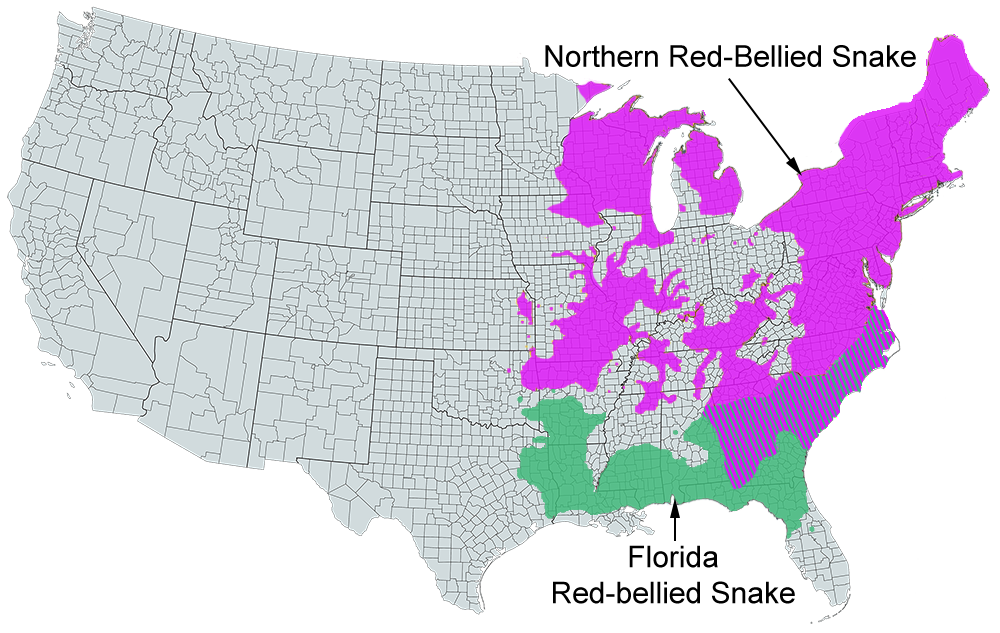

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.