Northern Rough Greensnake

Opheodrys aestivus

** Harmless **

Common Name: |

Northern Rough Greensnake |

Scientific Name: |

Opheodrys aestivus aestivus |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Opheodrys is derived from the Greek words ophios which means "serpent" and drys meaning "tree". |

Species: |

aestivus is Latin for "summer". |

Subspecies: |

aestivus is Latin for "summer". |

Vernacular Names: |

Bush snake, grass snake, green summer snake, green tree snake, green whip snake, huckleberry snake, keel-scaled green snake, magnolia snake, vine snake. |

Average Length: |

22 - 32 in. (56 - 81 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

37.3 in. (94.7 cm) |

Record length: |

45.6 in. (115.9 cm) |

Systematics: Originally described as Coluber aestivus by Carolus Linnaeus in 1766, based on a specimen sent to him by Alexander Garden from "Carolina." Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to Charleston, South Carolina. In the Virginia literature. Cope (1900) referred to this species as Cyclophis aestivus. All other authors in the Virginia literature have used the current nomenclature.

Recent subspecific designations for this species are controversial. Grobman (1984) described two new subspecies (O. a. carinatus, O. a. conanti) and resurrected one other (O. a. majalis [Baird and Girard]). However, these races have not been recognized by the herpetological community (e.g., Conant and Collins, 1991; Frost et al., 1992) because the distinctions among them were based on one or two differences in variable scale characters and on outmoded taxonomic practices. The subspecies O. a. conanti Grobman was restricted to the Virginia barrier islands. In the Virginia literature, it was included in Mitchell and Pague (1987) and Conant et al. (1990). Recognition of the Florida peninsular form described by Grobman (1984, Bull. Florida St. Mus. Biol. Sci. 29: 153–170) is supported by Plummer (1987, Copeia 1987: 483–485). Reviewed by Walley and Plummer (2000, Cat. Am. Amph. Rept. 718).

Description: A small- to moderate-sized, slender snake reaching a maximum total length of 1,159 mm (45.6 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia the maximum known SVL is 600 mm (23.6 inches) and maximum total length is 947 mm (37.3 inches). Tail length/total length in Virginia specimens was 32.2-42.4% (ave. = 37.5 ± 2.0, n = 157).

Scutellation: Ventrals 142-163 (ave. = 151.9 ± 4.2, n = 173); subcaudals 105-147 (ave. = 126.9 ± 8.4, n = 152); ventrals + subcaudals 177-302 (ave. = 278.1 ± 13.1, n = 152); dorsal scales keeled, scale rows 17 at midbody; anal plate divided; infralabials 7/7 (12.6%, n = 143), 7/8 (11.2%), 8/8 (68.5%), or other combinations of 6-9 (7.7%); supralabials 7/7 (91.8%, n = 147) or other combinations of 6-8 (8.2%); loreal scale present; preoculars 1/1; postoculars 2/2; temporal scales usually 1+2/1+2 (84.0%, n = 150) or other combinations of 1-3 (16.0%).

Coloration and Pattern: Dorsum of body, tail, and head uniformly green; venter, chin, and labial scales uniformly yellowish, yellowish green, or white to cream; green color fades to blue in preservative.

Sexual Dimorphism: Sexual dimorphism is expressed in body size and scutellation, but not in color or pattern. Average SVL in adult females (431.9 ± 59.8 mm, 303-600, n = 80) was longer than in adult males (387.3 ± 51.7 mm, 299-530, n = 72), and females reached a longer total length (947 mm) than males (892 mm). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.12. Tail length/total length averaged slightly higher in males (38.2 ± 1.9%, 34.0-42.4, n = 73) than in females (36.8 ± 1.8%, 32.2- 41.3, n = 82). Females weighed more (11-54 g, ave. = 26.7 ± 10.1, n = 18) than males (9-27 g, ave. = 16.3 ± 4.5, n = 22).

Females exhibited a higher average number of ventrals (females 153.1 ± 4.2, 144-163, n = 89; males 150.7 ± 3.8, 142-160, n = 81) than males but a lower average number of subcaudals (females 124.4 ± 8.2, 105-144, n = 78; males 129.7 ± 7.9, 112-147, n = 72). The average number of ventrals + subcaudals was slightly higher in males (280.3 ± 10.2, 259-300, n = 72; females 276.2 ± 15.3, 177-302, n = 78).

Juveniles: Juveniles are patterned and colored as adults, except that juveniles have a paler green color. At hatching, juveniles were 130-154 mm SVL (ave. = 143.4 ± 6.1, n = 20), 206-245 mm total length (ave. = 225.5 ± 9.3), and 1.4-2.0 g body mass (ave. = 1.8 ± 0.2).

Confusing Species: Rough Greensnakes may be confused only with Smooth Greensnakes (Opheodrys vernalis). The latter is similar in color but is a smaller snake and has smooth scales.

Geographic Variation: Numbers of ventral and subcaudal scales for males, females, and combined samples averaged less in populations on the Virginia barrier islands than in populations on the mainland.

Although there is a trend toward reduced ventral and subcaudal counts in populations on the Virginia barrier islands, the overlap in values among samples suggests that there is east-west clinal variation. Adequate samples from the mainland Eastern Shore of Virginia (not now available) and the Maryland portion of Delmarva should be compared to determine if the lower values reflect an island phenomenon or a peninsula effect.

| Sample | VA Barrier Islands | VA Coastal Plain | VA Piedmont | Western VA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ventrals | ||||

| Males | 147.8 ± 3.3 | 152.4 ± 4.9 | 151.5 ± 2.6 | 151.0 ± 3.7 |

| 142-153 (21) | 144-160 (28) | 147-155 (19) | 145-158 (13) | |

| Females | 148.8 ± 2.8 | 155.2 ± 3.3 | 154.2 ± 3.0 | 152.3 ± 5.1 |

| 144-154 (23) | 148-163 (39) | 147-159 (19) | 144-161 (08) | |

| Combined | 148.3 ± 3.1 | 153.9 ± 3.9 | 152.3 ± 3.1 | 151.1 ± 4.3 |

| 142-154 (44) | 144-163 (68) | 147-159 (38) | 144-161 (23) | |

| Subcaudals | ||||

| Males | 123.3 ± 6.8 | 132.2 ± 6.4 | 133.5 ± 8.7 | 128.8 ± 7.6 |

| 112-135 (19) | 117-144 (26) | 121-147 (17) | 119-142 (10) | |

| Females | 118.7 ± 6.9 | 125.8 ± 7.3 | 127.9 ± 9.5 | 126.1 ± 5.1 |

| 105-131 (21) | 111-137 (34) | 108-144 (16) | 119-132 (07) | |

| Combined | 120.9 ± 7.1 | 128.6 ± 7.5 | 130.8 ± 8.8 | 128.0 ± 6.6 |

| 105-135 (40) | 111-144 (61) | 108-147 (33) | 119-142 (18) |

* NOTE: Upper number is sample mean ± 1 standard deviation; lower number is minimum-maximum (sample size in parentheses).

Biology: Rough Greensnakes are aptly named Opheodrys because they are primarily arboreal. They have been found in open deciduous forest, mixed hardwood-pine forest, old fields, myrtle thickets, and the wrack zone of barrier islands. The microhabitat includes deciduous trees, shrubs, hedgerows, and fields with grass cover and small shrubs. Rough Greensnakes are often found in trees and shrubs lining lakes and ponds. Richmond (1952) found several specimens in water; one was "completely under water resting on a submerged bush." These snakes are occasionally found in urban areas, and many are killed by lawn mowers presumably while they are foraging in the grass. They are diurnal and sleep at night coiled on branches. Werler and McCallion (1951) noted that O. aestivus was active every month of the year except December-February, and Clifford (1976) recorded an activity season of May-September for Amelia County. Museum record extremes are 6 April to 28 October, with one unspecified record for November.

Opheodrys aestivus aestivus eats exclusively invertebrate prey. Uhler et al. (1939) found the following in two snakes from the George Washington National Forest: spur-throated grasshoppers, long-horned grasshoppers, noctuid moth caterpillars, butterfly caterpillars, harvestmen, and land snails. Sphecid wasps, wood roaches (Parcoblatta spp.), and unidentified spiders were found in other Virginia specimens. The prey of this snake falls into three major groups: lepidoptera (larvae), orthoptera (grasshoppers and crickets), and arachnids (spiders and harvestmen) (Brown, 1979; Plummer, 1991). Known predators of O. aestivus in Virginia are loggerhead shrikes (Lanius ludovicianus), hawks (Buteo spp.), and domestic cats (Mitchell and Beck, 1992).

Opheodrys aestivus aestivus is oviparous and lays smooth-shelled eggs in June and July (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b). The smallest mature male in the Virginia sample was 299 mm SVL and the smallest female was 303 mm SVL. Mating occurs in spring (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b) and fall. Richmond (1956) reported a fall mating date of 17 September in New Kent County and described the mating behavior of a pair of snakes in a pecan tree:

[T]he snakes [already in copula] were rapidly weaving in and out of the leaves, occasionally crossing to other twigs. At intervals they" would pause, or crawl slowly, then suddenly go into the fast swirling motion that first attracted my attention. Although their movement was fast, the total distance moved in 15 to 20 minutes was only 3 feet. After a period of being motionless, the male left and climbed higher in the tree.

Females laid 3-12 eggs (ave. = 6.2 ± 2.1, n = 19 clutches) inside decaying logs, under rocks in loamy soil, and under boards on sandy soil. Plummer (1989) found that females in Arkansas and South Carolina laid eggs in tree cavities as high as 3 m above the ground and that some females returned to the same cavities in subsequent years. Egg-laying dates for Virginia snakes were between 12 June and 25 July, all but one of eight in July. Embryological development is more advanced in this genus at the time of egg laying than other Virginia snakes. Consequently, laboratory incubation times are relatively short--22-47 days. One incubation period of 81 days may have been due to cool temperatures (C. A. Pague, pers. comm.). Eggs were 26.0 ± 5.2 x 10.0 ± 0.7 mm (length 21.4-33.6, width 9.3-11.1, n = 10) and weighed 1.2-2.4 g (ave. = 1.8 ± 0.6, n = 10). Known hatching dates are 31 July - 13 September. Analyses of annual reproductive cycles of males (Aldridge et al., 1990) and females (Plummer, 1985c) have been published only for Arkansas populations.

Werler and McCallion (1951) mentioned that this was one of the most common snakes in the Virginia Beach area. Clifford (1976) listed 8 green snakes out of a total of 278 snakes recorded in Amelia County during 1972-1975. Martin (1976) listed 6 individuals of this species out of 545 seen on the Blue Ridge Parkway and Skyline Drive in a 3-year period. My subjective view is that populations of this species have declined over the past two to three decades, possibly in response to herbicide and pesticide applications that affect the prey of this snake (Ernst and Barbour, 1989b).

Plummer (1985a, 1985b) found that the population density of O. aestivus around an Arkansas lake was 430 per hectare. Growth occurred in May through September, and females grew faster (1.0-1.2 mm per day) than males (0.1 mm per day). The probability of surviving from one year to the next was 39% for males, 49% for females, and 21% for juveniles. This is a docile species that will not bite. It seeks escape from predators by climbing into dense vegetation where it is difficult to see.

Remarks: Other common names used in Virginia are keeled green snake (Hay, 1902); green whip snake (Burch, 1940); garden snake, grass snake, and vine snake (Linzey and Clifford, 1981); and green garter (Brothers, 1992).

Conservation and Management: The decline of O. aestivus populations over the past several decades should be cause for alarm. If my perception of the trend is accurate, loss of prey via pesticide use or other forms of pollution may be one cause. Other causes of population declines include mortality on roads by increased numbers of vehicles, and predation by domestic and feral cats. Although its status in Virginia seems secure at this time based on the number of known occurrences, increases in the amount of habitat loss, kinds of pesticides used, and number of introduced predators will only continue the downward trend. This species should be monitored wherever possible. Maintenance of this species requires the presence of hardwood trees and shrub vegetation along ecotones and freshwater wetlands.

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Bath

Bedford

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buchanan

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Carroll

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Clarke

Culpeper

Cumberland

Dickenson

Dinwiddie

Essex

Fairfax

Fauquier

Fluvanna

Franklin

Gloucester

Goochland

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Loudoun

Louisa

Lunenburg

Madison

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Middlesex

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Russell

Scott

Shenandoah

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Warren

Washington

Westmoreland

Wise

Wythe

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Chesapeake

Fredericksburg

Hampton

Lynchburg

Manassas

Newport News

Norfolk

Poquoson

Portsmouth

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Williamsburg

Winchester

Verified in 84 counties and 15 cities.

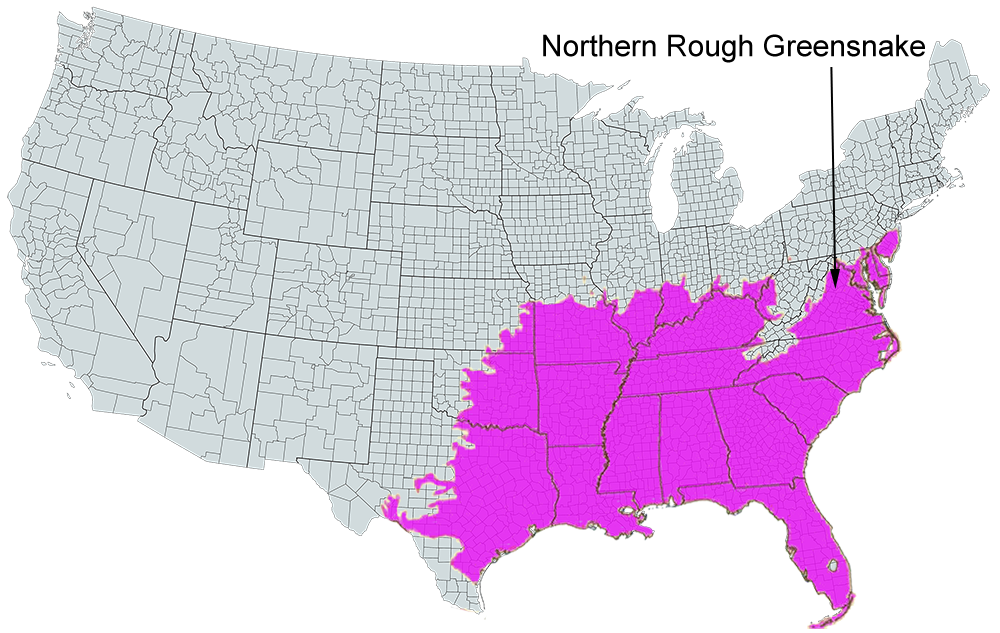

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.