Southern Ring-necked Snake

Diadophis punctatus punctatus

Common Name: |

Southern Ring-necked Snake |

Scientific Name: |

Diadophis punctatus punctatus |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Diadophis is derived from the Greek words diadem which means "headband" and ophis which means "snake". |

Species: |

punctatus is derived from the Latin word punctum which means "spot". This refers to the ventral spotting. |

Subspecies: |

punctatus is derived from the Latin word punctum which means "spot". This refers to the ventral spotting. |

Vernacular Names: |

Punctuated viper; ring snake |

Average Length: |

10 - 14 in. (25.4 - 36 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

19.5 in. (49.5 cm) |

Record length: |

27.8 in. (70.6 cm) |

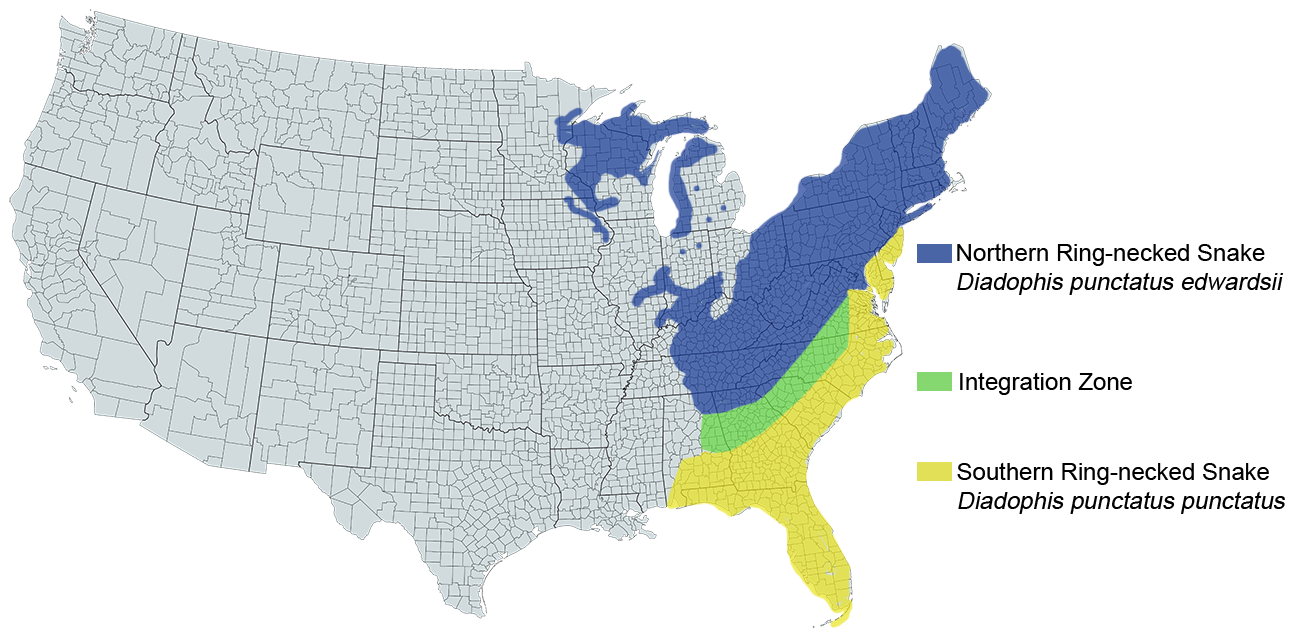

Systematic: Originally described as Coluber punctatus by Carolus Linnaeus in 1755 based on a specimen sent to him by Alexander Garden from South Carolina. The type locality was restricted to Charleston, South Carolina, by Schmidt (1953). The genus Dladophis was first used for this species by Baird and Girard (1853). All authors in the Virginia literature have used the current nomenclature. Two subspecies occur in Virginia: D. punctatus punctatus (Linnaeus) and D. punctatus edwardsii (Merrem).

Diadophis punctatus punctatus (Linnaeus) is the original subspecies. Diadophis punctatus edwardsii (Merrem) was first described as Coluber edwardsii by Blasius Merrem in 1820, based on a specimen collected by William Bartram in "Pennsylvania." The type locality was restricted to the vicinity of Philadelphia by Schmidt (1953). Barbour( 1919)first relegated this form to a subspecies of D. punctatus.

Description: A small, slender snake reaching a maximum total length of 706 mm (27.8 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 400 mm (15.7 inches) and maximum total length is 495 mm (19.5 inches). In this study, tail length/total length averaged 21.3 ± 2.1% (15.7-29.1, n = 323).

Scutellation: Ventrals 132-172 (ave. = 154.1 ± 7.7, n = 353); subcaudals 35-68 (ave. = 53.4 ± 6.0, n = 322); ventrals + subcaudals 177-229 (ave. = 207.5 ± 11.4, n = 322); dorsal scales smooth, scale rows 15 (100%, n = 337) at midbody; anal plate divided; infralabials 8/8 (71.2%, n = 340), 7/7 (14.7%), or other combinations of 6-10 (14.1%); supralabials 8/8 (63.7%, n = 339), 7/7 (19.5%), 7/8 or 8/7 (14.4%), or other combinations of 6-9 (2.4%); loreal present; preoculars 2/2; postoculars 2/2; temporals usually 1 +1/1 + 1 (94.1%, n = 337), 1+2/1+2 (3.2%), or other combinations of 1 and 2 (2.7%).

Coloration and Pattern: Body uniformly bluish black to slate gray or brownish, with a cream to yellow collar across neck; collar complete or broken (or constricted) at middorsal line; venter cream to yellow and immaculate, or patterned with a single midventral row of small black spots to large half-moon-shaped spots; head black with white supralabials and a white chin. Some specimens have black spots in the labial scales and on the chin. The head is flattened in individuals from the mountains and rounded in those from the Piedmont and Coastal Plain.

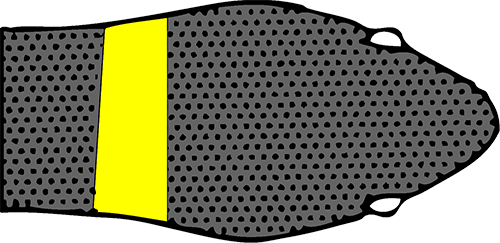

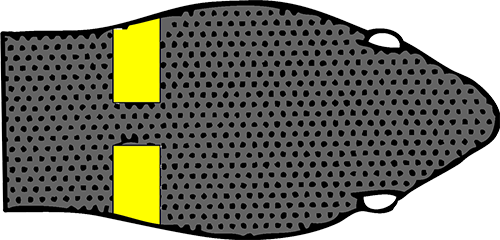

Subspecies: Diadophis punctatus edwardsii usually has a complete collar, and a venter that is either completely unpatterned or with several to numerous small black spots along the midventral line. Diadophis punctatus punctatus has a broken collar and a single row of large, black half-moons along the midventral line. Intergrades occur in parts of eastern Virginia and these subspecies differ in size and scutellation (see "Geographic Variation").

|

|

Northern Ring-necked Snake |

Southern Ring-necked Snake |

Sexual Dimorphism: There are no sexual differences in color or pattern. Adult male SVL was 183-358 mm (ave. = 262.3 ± 43.0, n = 111) and female SVL was 219-400 mm (ave. = 300.0 ± 49.7, n = 109). Sexual dimorphism index was 0.14. Tail length/total length averaged higher in males (22.3 ± 1.7%, 16.6-29.1, n = 174) than in females (20.2 ± 2.0%, 15.7-28.8, n = 147). Number of ventral scales was slightly higher in females (138-172, ave. = 156.0 ± 6.4, n = 161) than males (132-165, ave. = 150.7 ±7.1, n = 190), whereas number of subcaudal scales was slightly higher in males (35-68, ave. = 54.8 ± 6.0, n = 171) than females (37-64, ave. = 51.8 ± 5.7, n = 149). Number of ventral + subcaudal scales was similar between sexes (males 177-223, ave. = 205.5 ± 11.8, n = 171; females 179-229, ave. = 209.7 ± 10.6, n = 149).

Juveniles: Hatchlings are patterned as adults but the body is uniformly colored black or blue-black and the venter is usually white. At hatching, juveniles were 91-128 mm SVL (ave. = 107.5 ± 11.6, n = 18), 108-159 mm total length (ave. = 131.7 ± 16.4), and 0.6-1.1 g body mass (ave. = 0.84 ± 0.12).

Confusing Species: Diadophis punctatus is usually identified correctly because of the uniformly colored body and head and the bright collar across the neck. Juveniles can be mistaken for neonates of Storeria dekayi, Storeria occipitomaculata, and Haldea striatula, but all of these have keeled scales.

Geographic Variation: Diadophis punctatus reached larger average SVLs in the upper and lower Ridge and Valley regions (257.1 ± 62.0 mm, 93-390, n = 118; 257.1 ± 58.9 mm, 137-340, n = 55, respectively) than in the upper Piedmont (226.6 ± 62.2 mm, 92-320, n = 22), lower Piedmont (209.0 ± 74.0 mm, 93-318, n = 26), and southeastern Coastal Plain (208.6 ± 37.9 mm, 130-295, n = 47). The largest Ring-necked Snakes were found in the Appalachian Plateau region (ave. SVL = 265.0 ±72.4 mm, 135-400, n = 21). Number of ventral scales increased from an average low of 142.5 ± 5.8 (132-160, n = 47) in the southeastern Coastal Plain to an average high of 159.2 ± 4.9 (151-170, n = 21) on the Appalachian Plateau. A similar trend occurred in number of ventrals + subcaudals (SE Coastal Plain ave. - 185.7 ± 5.7,177-210, n = 46; Appalachian Plateau ave. = 216.7 ± 4.5, 210-226, n = 20).

The highest frequencies of snakes with broken collars (D. p. punctatus) were in the southeastern Coastal Plain: 51.1% of 47 broken, 27.7% constricted, and 21.3% complete. Large, black half-moons on the venter predominated in the south- eastern Coastal Plain sample (83.0% of 47). The remainder of the individuals in this sample had small spots or none at all (17.0%). In the Coastal Plain sample (n = 23) north of the James River, 13.0% had broken collars and 87.0% had complete collars. In this area, 27.8% of 18 had large half-moons on the venter and 72.2% had small spots or were immaculate. Immediately west of the Fall Line in the lower Piedmont, 3.8% of 26 snakes had constricted collars and 96.2% had complete collars. Large spots on the venter occurred in 26.9% of the sample; 73.1% had small spots or were immaculate. The zone of intergradation extends from the northern and middle peninsulas south-westward to an area encompassed by Mecklenburg County on the west and Southampton County on the east. Populations in this zone produced individuals that showed combinations of all the character variations. Ring-necked Snakes found north and west of this zone were D. p. edwardsii. Snakes southeast of this zone were D. p. punctatus. In their analysis, Blem and Roeding (1983) suggested that, except for the cities of Suffolk, Norfolk, and Virginia Beach, the intergrade zone was in the shape of a triangle formed by the James River, the Fall Line, and the southern Virginia border. Conant (1946) determined that Ring-necked Snakes in southeastern Virginia were true D. p. punctatus and that there was an intergrade zone on Delmarva and in southern New Jersey. Of the two specimens from the Eastern Shore in Virginia, the collar was complete in one and constricted in the other, and the ventral patterns of both showed a series of small black dots, thus supporting Conant's analysis. The entire intergrade zone between these two subspecies has yet to be fully studied.

Biology: Ring-necked Snakes are secretive and are usually found associated with hardwood or mixed hardwood-pine forests. They are inhabitants of leaf litter and the upper soil horizon community. They are seldom encountered in the open; most are found under all types of objects, including logs, rocks, boards, and debris. Diadophis punctatus is found in urban and agricultural areas, as well as in mixed forest types. Diadophis p. punctatus usually occurs where some degree of moisture is present, such as in junk piles and under logs in moist lowlands and floodplains. Hutchison (1956) found D. p. edwardsii in the twilight zone of caves. This subspecies is frequently found under rocks in dry habitats in the forest, such as on roadcuts and exposed rocky areas in the mountains. Some surface movement occurs at night, as several ringneck snakes have been killed on roads by vehicles during that time. Martin (1976) recorded only 15 ring-necked snakes among the 545 snakes observed along the Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park and Blue Ridge Parkway in a 3-year period. Clifford (1976) found only one D. punctatus in a 4-year period in Amelia County. This species is known to be active 10 April through 20 October in Virginia, but may be found at other times of the year depending on the weather. The activity season is as much as 2 months shorter in the mountains than it is along the coast. Body temperatures of 21 individuals found in April and July under exposed rocks in the mountains were 18.6-31.0°C (ave. = 24.1 ± 3.2); ambient temperatures were 17.2-18.0°C (ave. = 17.6 ± 0.4, n = 18).

Three prey types form the majority of the diet of this snake: earthworms, salamanders, and lizards. The following prey have been recorded for Virginia D. punctatus: earthworms, Northern Two-lined Salamanders (Eurycea bislineata), Red-backed Salamanders (Plethodon cinereus), White-spotted Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon cylindraceus), Northern Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon glutinosus), and Little Brown Skinks (Scincella lateralis). Uhler et al. (1939) found E. bislineata and P. cinereus in four of five specimens examined from the George Washington National Forest. The ants and other arthropods listed in Uhler et al. (1939) were probably the remains of salamander stomach contents. Ernst and Barbour (1989b) summarized the known prey of this species in eastern North America. Vertebrate prey are killed by constriction. Known predators of Virginia Ring-necked Snakes are Northern Black Racers (Coluber constrictor) and free-ranging domestic cats (Mitchell and Beck, 1992). In a long-term study of D. punctatus in Kansas, Fitch (1975) found that great-horned owls (Bubo virginianus), hawks (Buteo spp.), four species of snakes (Agkistrodon contortrix, C. constrictor, Crotalus horridus, Lampropeltis triangulum), and Bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) had taken Ring-necked Snakes as prey.

Diadophis punctatus is oviparous, laying 2-7 eggs (ave. = 4.2 ± 1.5, n = 20) under rocks, and in and under logs where the substrate is moist. A female from Fairfax County laid the maximum known clutch size of 10 eggs (C. H. Ernst, pers. comm.). The number of eggs is positively related to the size of the female (Fitch, 1975). Fitch (1975) recorded spring and fall mating dates during his study in Kansas. Copulation was observed in the field in Virginia on 16 September (C. A. Pague, pers. comm.). Eight egg-laying dates were recorded between 16 June and 21 July. Natural egg-laying was observed in Lee County on 8 July (C. A. Pague, pers. comm.). Ring-necked Snake eggs are smooth, and averaged 27.7 ± 6.2 x 8.8 ± 0.7 mm (length 22.2-36.0, width 7.9-9.3, n = 5) in size and 1.32 g (1.30-1.33, n = 2) wet mass. Laboratory incubation time was 45-58 days and recorded hatching dates were between 2 and 30 August. The smallest mature female in the Virginia sample was 218 mm SVL; the smallest mature male was 180 mm. Groves (1978) reported that one of three eggs laid by a female from Page County contained twin hatchlings. The population ecology of this species in Virginia has not been studied, but Fitch (1975) estimated population densities of 719-1,849 individuals per hectare in Kansas. Populations of D. punctatus in Virginia appear to be larger in the mountains than in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain, but this may be a function of the number of aggregation sites in the former compared to the latter. Fitch (1975) noted that Ring-necked Snakes do not always use sites that allow us to catch them, as many snakes seek shelter beneath mats of vegetation.

Ring-necked Snakes do not bite when caught but will release foul-smelling feces and musk from anal glands. Exaggerated tail coiling, a defensive behavior that detracts a potential predator away from the head, is seen in subspecies that have the ventral surface of the tail brightly colored (Conant, 1975; Fitch, 1975). This behavior has not been seen in Virginia D. punctatus, although the tail is often partially coiled when these snakes are captured. Fitch (1975) found that most movements made by ringneck snakes in Kansas were less than 250 m in length. This suggests that these snakes maintain large home ranges for their body size.

Remarks: Other common names are fodder snake (Dunn, 1915a); common ring neck snake (Carroll, 1950); and ring snake, baby king snake, red-belly snake, and yellow-belly ring snake (Linzey and Clifford, 1981). Linzey and Clifford (1981) noted that some people consider D. punctatus to be the young ofLampropeltis getula, whose crossbands are added as they grow. These authors correctly point out that Eastern Kingsnakes are born with the pattern they keep for life.

The lack of locality records on the lower portions of the Eastern Shore and middle peninsula is puzzling. Is this a function of collecting effort, bad luck, or true zoogeographical patterns?

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Campbell

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Fairfax

Fluvanna

Goochland

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Isle of Wight

James City

Mecklenburg

New Kent

Northampton

Nottoway

Southampton

Surry

York

CITIES

Charlottesville

Chesapeake

Hampton

Petersburg

Richmond

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Williamsburg

Verified in 21 counties and 8 cities.

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.