Timber Rattlesnake

Crotalus horridus

*** VENOMOUS ***

Venomous Snake Bite Information

Common Name: |

Timber Rattlesnake |

Scientific Name: |

Crotalus horridus |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Crotalus is derived from the Latin word crotalum which means "rattle". |

Species: |

horrid is Latin for 'dreadful'. |

Vernacular Names: |

American viper, bastard rattlesnake, black rattlesnake, common rattlesnake, eastern rattlesnake, great yellow rattlesnake, mountain rattlesnake, northern banded rattlesnake, northern rattlesnake, pit viper, rock rattlesnake, velvet tail, yellow rattlesnake. |

Average Length: |

30 - 60 in. (90 - 152 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

67.1 in. (170.5 cm) |

Record length: |

74.5 in. (189.2 cm) |

Timber Rattlesnake Populations

Systematics: Originally described as Crotalus horridus by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758, based on a specimen from "America." Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to New York City. Pierre-Andre Latreille first described the canebrake rattlesnake, Crotalus atricaudatus, as a full species in Sonnini and Latreille (1802), based on a description sent to him from "Carolina" by Louis-Augustin-Guillaume Bose (Gloyd, 1935). This name was not recognized, however, for over a century, as most authors considered it to be synonymous with Crotalus horridus (e.g.. Cope, 1900; Gloyd, 1940). Gloyd (1935) resurrected C. atricaudatus Latreille but showed that it should be a subspecies of C. horridus. This combination was subsequently followed in most of the Virginia literature (e.g., Werler and McCallion, 1951; Wood, 1954a; Conant, 1958,1975; Mitchell, 1974b; Williamson, 1979; Tobey, 1985). Extensive phenotypic variation in the western portion of this species' range caused Pisani et al. (1972) to recommend that the subspecies atricaudatus no longer be recognized. Many authors have followed this recommendation (e.g., Collins and Knight, 1980; Martof et al., 1980; Schwab, 1988c; Conant and Collins, 1991). A later study by Brown and Ernst (1986) suggested that the two subspecies should be recognized in the southeastern portion of the species' range. Pisani et al. (1972, Trans. Kansas Acad. Sci. 75: 255–263) conducted a multivariate analysis of variation in C. horridus and concluded that characters tended to be clinal and recommended against recognition of the two subspecies. Brown and Ernst (1986, Brimleyana 12: 57–74) countered that morphology in the eastern part of the range supported recognition of coastal plain and montane subspecies. Clark et al. (2003, J. Herpetol. 37: 145–154) identified three mitochondrial DNA lineages separated by the Appalachian and Allegheny Mountain ranges that did not correspond with the classic arrangement of subspecies within C. horridus

Description: A large, venomous snake reaching a maximum total length of 1,892 mm (Conant and Collins, 1991), with one or more loose keratinized segments on the base of the tail forming a rattle. In Virginia, maximum known snout-vent length (SVL) is 1,600 mm (63.0 inches) and maximum total length is 1,705 mm (67.1 inches). In the present study, tail length/total length was 4.9-14.6% (ave. = 7.6 ± 1.8, n = 88).

Scutellation Ventrals: 154-173 (ave. 164.5 ± 3.7, n = 109); undivided subcaudals 17-28 (ave. = 22.2 ± 2.6, n = 97); ventrals + subcaudals 177-200 (ave. = 186.9 ± 3.8, n = 95); dorsal scales strongly keeled, scale rows 18-26 at midbody, but usually 23 or 25; anal plate single; infralabials 15/15 (20.3%, n = 79), 15/14 (16.5%), 14/14 (17.7%), 13/14 (13.9%), or other combinations of 12-16 (31.6%); supralabials 13/14 (32.1%, n = 81), 14/14 (27.2%), 15/14 (12.3%), 13/13 (13.6%), or other combinations of 11-15 (14.8%); loreal scales 1-3, but usually 2; preoculars 1-2 on each side; postoculars 2-5 on each side; temporal scales variable, 3-4 in each column.

Coloration and Pattern: Dorsum highly variable in color; most individuals possess a series of 16-27 (ave. = 22.6 ± 1.9, n = 93) zigzag-shaped blotches and crossbands on dorsum; blotches and crossbands dark brown to black; along posterior dorsum middorsal blotches contact lateral blotches and form chevrons (zigzag-shaped crossbands); body color pinkish to nearly black; three color varieties common: (1) "canebrake phase," with dark-brown to black blotches and chevrons on pinkish to light-tan body, plus a brown or chestnut middorsal stripe and a brown eye-jaw stripe; (2) "yellow phase," with yellow head and dark- brown to black blotches and chevrons on yellowish-brown body; and (3) "black phase," with black head and black blotches and chevrons on dark-brown to nearly black body. Some individuals can be assigned to one of these categories but many others possess characteristics of all three. Completely black individuals have been reported. The venter is cream in color, variously peppered with black. The tail is black or brown with black bands when visible.

Sexual Dimorphism: Crotalus horridus males' SVL (790-1,220 mm, ave. = 956.0 ± 113.0, n = 51) averaged larger than females' SVL (690-1,025 mm, ave. = 866.7 ± 89.1, n = 30), and males reached a longer total length (1,320 mm) than females (1,090 mm). Sexual dimorphism index was -0.10. Average tail length/total length of males of the southeastern populations (4.9-14.2%, ave. = 7.7 ± 1.6, n = 63) was slightly larger than the female ratio (5.2-14.6%, ave. = 6.9 ± 2.1, n = 23).

Average number of ventrals in males (163.6 ± 3.3, 154-173, n = 73) was slightly lower than that in females (166.6 ± 3.7, 154-172, n = 34), whereas the average number of subcaudals was higher (males 23.3 ± 2.0, 18-28, n = 68; females 19.3 ± 1.7, 17-23, n = 27). The average number of ventrals + subcaudals was similar between sexes (males 187.0 ± 4.0, 177-200, n = 67; females 186.7 ± 3.6, 177-192, n = 26). The number of body blotches and crossbands was also similar (males 22.5 ± 1.9, 21-26, n = 59; females 22.1 ± 1.8, 18-25, n = 28).

Juveniles: Juveniles are patterned as adults at birth. Some C. horridus juveniles may possess a middorsal stripe and an eye-jaw stripe, although these fade with age in many individuals. Neonates have only one basal segment of the rattle, the button. They are gray to brown or pinkish in color with black or dark-brown chevrons. Crossbands on the tail are evident at birth, but accumulation of black pigment increases with age and causes the tails of most snakes to become all black. In total length, Crotalus horridus neonates were 216-340 mm, males averaging 292 ± 15 mm (240-340, n = 31) and females averaging 280 ± 15 mm (216-310, n = 31) (W. H. Martin, pers. comm.).

Confusing Species: Few snakes are confused with C. horridus because they lack the rattle. Juveniles may be confused with juvenile Agkistrodon piscivorus and A. contortrix, but these have yellow tail tips.

Geographic Variation: Crotalus horridus in southeastern Virginia differs from C. horridus in mountainous regions by body color and number of dorsal scale rows, and by having a distinct middorsal stripe and an eye-jaw stripe in adults. The yellow and black phases, as well as intermediate colors between them, occur only in the western portion of the range in Virginia. Isolated populations inhabiting the southwestern Piedmont and parts of the Blue Ridge escarpment exhibit some characteristics typical of the atri- caudatus pattern. Southeastern populations had slightly higher counts of ventral scales (161-173, ave. = 167.0 ± 4.2, n = 5) and subcaudal scales (22-25, 24.4 ± 3.0, n = 7) than montane populations (ventrals 154-172, ave. = 164.4 ± 3.6, n = 104; subcaudals 17-26, 22.0 ± 2.5, n = 90). The average number of ventrals + subcaudals was higher in the southeast (185-200, ave. = 193.6 ± 5.5, n = 5) than in the mountains (177-194, ave. = 186.5 ± 3.4, n = 90), as was the number of dorsal scale rows (SE 22-25, ave. = 24.4 ± 1.1, n = 7; mts. 18-26, ave. = 23.1, n = 79). Inadequate samples are available to determine whether intermediate values occur in southwestern Piedmont and southern Blue Ridge Mountains populations.

Biology: In western Virginia, Crotalus horridus inhabits upland hardwood and mixed oak-pine forests in areas with ledges or talus slopes. Ledges and exposed areas are usually facing within 45° of south to allow maximum exposure to the sun during spring and fall. Habitat during summer is in open woods, grass fields, and secondary growth. In southeastern Virginia, C. horridus occupies hardwood and mixed hardwood-pine forests, cane fields, and ridges and glades of and adjacent to swampy areas. Rattlesnakes are usually terrestrial, but occasionally ascend low shrubs to obtain prey (Klauber, 1972). Cooper (1960) found a specimen of C. horridus in the mouth of a cave in Highland County. C. horridus usually overwinter singly or in small numbers (Wood, 1954a), but the life of a Timber Rattlesnake in other pards of the state centers around communal-ancestral dens (hibernacula) and birthing rookeries (Martin, 1988). Most of the information on the seasonal ecology of Timber Rattlesnakes is based on the long-term studies of W. H. Martin, III. The following summary is from Martin (1988, 1992). Den sites are found at elevations of 200-1,200 m on steep slopes of 30-45°, and occur in fissures in ledges or in talus or scree on bare rock or soil. Individual rattlesnakes usually return to the same den each year. Snakes enter hibernation sites 26 September-18 October, but some stragglers remain on the surface until 5 November. Hibernation lasts an average of 204 days, from 10 October to 1 May. In spring, emergence is sporadic, with general mass emergence between 18 April and 12 May, depending on the weather. The earliest emergence date was 8 March and the latest was 2 June. Migration to summer home ranges occurs on average in mid-May. Migration distances were 0.4-2.8 km for adult males, 0.4-2.6 km for adult females, and 0.4-2.5 km for juveniles. Home ranges were 5.0 km in diameter for adult males, 4.3 km for adult females, 1.0 km for reproductive females, and 3.7 km for juveniles. Active snakes away from hibernacula were found May-October. Timber rattlesnakes are diurnal in spring and fall, and nocturnal in summer until about midnight.

Timber rattlesnakes are primarily predators of mammals but will eat some frogs and birds. The following prey types have been recorded for Virginia specimens: mammals-woodland jumping mice (Napaeozapus insignis), white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus), deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), southern red-backed voles (Clethrionomys gapperi), meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus), woodland voles (Microtus pinetorum), eastern woodrats (Neotoma floridana), chipmunks (Tamias striatus), gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis), southern flying squirrels (Glaucomys volans), eastern cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus), southern bog lemmings (Synaptomys cooperi), masked shrews (Sorex cinereus), northern short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda), and least shrews (Cryptotis parva); birds-yellowbill cuckoos (Coccyzus americanus), brown thrashers (Toxostoma rufum), wood thrushes (Hylocichla mustelina), cedar waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum), black-throated blue warblers (Dendroica caerulescens), ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapillus), rufous-sided towhees (Piplio erythrophthalmus), grasshopper sparrows (Ammodramus savannarum), and unidentified sparrows and warblers (Uhler et al., 1939; Bailey, 1946; Smyth, 1949). A total of 87% of the 141 specimens from the George Washington National Forest contained small mammals and 13% contained birds (Uhler et al., 1939). White-footed mice are taken at night and chipmunks during the day (Martin, 1988). Southeastern Timber Rattlesnakes are known to eat squirrels and small raccoons (Procyon lotor) (Lederer, 1672; Martin and Wood, 1955). Rattlesnakes are occasionally killed by white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), sheep, dogs, hogs, and red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) (Klauber, 1972). Klauber included several observations of Eastern Ratsnakes (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) killing rattlesnakes, but also noted that they can occupy the same den. Juvenile C. horridus are sometimes eaten by domestic chickens and turkeys (Klauber, 1972). Humans are the premier killers of rattlesnakes.

Timber Rattlesnakes are viviparous and bear living young. Three to 13 young (ave. = 7.6 ± 3.2, n = 8) are born in September through early October. Martin's (1988, 1992, 1993) notes are summarized below. Litters of 3-16 young (ave. = 7.8 ± 2.6, n = 85) were born at 2-, 3-, or 4-year intervals, depending on nutrition and age of the female. Females reached maturity at 4-5 years of age and at about 686 mm SVL, whereas males matured at about 4-5 years and 778 mm SVL. Courtship behavior was observed on 21 August, and 5 and 13 September; copulation occurred on the latter two dates. Male combat was seen on 31 July and 25 August. Birthing took place at ancient communal rookeries located at or near den sites. Rookeries were ledges or talus slopes that afforded cover for females and their young. Known birth dates are between 9 August and 16 October. Neonates stayed with females for up to 2 weeks and both subsequently foraged for prey until hibernation. Young snakes followed scent trails of adults to hibernacula. Comparatively little is known about reproduction in southeastern Virginia populations. Known litter size is 7-18 (11.8 ± 4.4, n = 6). Mating was observed in captivity on 3 September and known birth dates are 27 August and 12 September (Martin and Wood, 1955). In South Carolina, litters of 10-16 were born at 2- to 3-year intervals, depending on the nutrition of the female; maturity was reached at 6 years of age and about 1,000 mm SVL for females and 900 mm SVL for males (Gibbons, 1972).

The population ecology of the timber rattlesnake has been studied in Shenandoah National Park by W. H. Martin, III. The following summarizes data in Martin (1988) for the period of 1973-1987. Total population size was estimated to be 5,400-6,700 snakes for the park. Given the heavy exploitation since the 1930s, this estimate was probably 35-50% of original population size. Natural mortality for young-of-the-year was 50% and for the second year 66%, and was caused by failure to find food or adequate hibernacula. Adult mortality was 10% per year mostly due to human activities. The oldest snakes were 30-50 years of age.

Remarks: Other common names in Virginia are rattlesnake (Dunn, 1915a, 1918), banded rattlesnake (Uhler et al., 1939), and diamondback.

Myths abound about the behavior of rattlesnakes; several are mentioned in the introduction to the snake accounts. Perhaps the most common fallacy is that the number of rattles indicates the age of the snake. A segment is added at each shedding event. Juveniles shed an average of 8 times during the first 5 years and adults average 1.2-1.3 times annually (Martin, 1988). Even if the rattles did not break, as they easily do, simply counting the segments would overestimate the age. Martin (1993) provides a methodology for estimating the ages of adult females from rattle segments.

Individuals of Crotalus horridus may have occurred historically on the Delmarva peninsula. The only evidence is a place name (Rattlesnake Island) north of the Maryland-Virginia state line and a note from A. B. Fuller to R. Conant, dated 6 November 1948, that relates the observations of a then-88-year-old Dr. Downing (R. Conant, pers. comm.). Dr. Downing noted that one was killed "a long time ago" near Bell Haven, Accomack County; another was killed "about 40 years ago" about a mile west of Jamesville, Northampton County; and several rattlesnakes were found when the railroad cut through a swamp in Accomack County. If Timber Rattlesnake populations occurred on the Eastern Shore, then all of them have become extinct. Additional historical records would be of interest.

Conservation and Management: Crotalus horridus appears to be somewhat stable in scattered locations in the Virginia mountains and, although it has declined substantially from historical numbers, may not currently warrant legal protection. The primary causes of the decline of C. horridus populations are habitat loss and direct removal from dens and birthing rookeries by humans. This species has declined dramatically in all northeastern states, is extirpated in two, and is protected in most of the rest (Brown, 1993).

References for Life History

Southeastern "Canebrake" Populations

Virginia Wildlife Action Plan Rating Tier II - Very High Conservation Need - Has a high risk of extinction or extirpation. Populations of these species are at very low levels, facing real threat(s), or occur within a very limited distribution. Immediate management is needed for stabilization and recovery.

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: In Virginia, most adults are 1.2-1.4 meters in total length *11623*. The head is triangular and pits are located below the midpoints between each eye and nostril *11623,9286*. There is a postocular stripe that varies from light orange to dark brown and a reddish middorsal stripe that extends for the entire length of the body *882,11623*. The pupil of the eye is vertical and elliptical. The tail is tipped with a rattle. The body color is pinkish, gray, yellow, or light brown with a series of black chevrons. The ventor is cream in color and may be lightly peppered with black. The tail is black. Males grow to larger sizes than females. Males in South Carolina were 1220-1400 mm in snout-vent length (SVL) and 1235-2490 gram in body weight compared to females of 1170-1280 mm SVL and 1033-1546 gram body weight. Juveniles are 305-356 mm total length at birth and are patterned as the adults and are usually pinkish. Neonates possess a prebutton prior to the first shed, and a single button appears after the first shed. Additional segments forming the rattle are added at each ecdysis *11623,9286*.

REPRODUCTION: According to Savitzky's research of the populations in southeastern Virginia, most females are suspected to reproduce approximately every 4 years, or possibly every 3 to 5 years *11623*. They bear their young live and have litters of seven to 16 young *9286,11623*. The females give birth to their first litter in their sixth year when they reach a length of about 40 inches *9286,10760*. The males are sexually mature in their fourth year. Courtship and mating occur in mid-summer to early fall of the year before birth *11623*. The young are born in late August or early September *1023,1101,858,10760*.

BEHAVIOR: This species is diurnal in the spring and fall, crepuscular and nocturnal in the summer *1023,946*. Snakes enter hibernacula in October or November and emerge in March, April, or May *11623*. Unlike the communal den characteristic of the timber rattlesnake, overwintering occurs singly or in small numbers in stumps. This species is usually terrestrial but will ascend low shrubs. They are primarily tertiary level predators of small mammals but will consume other vertebrates. They are known to eat squirrels, rats, mice, cottontail rabbits, six-lined racerunners, skinks and birds. They are not territorial *9286,11623*.

LIMITING FACTORS: This species is found in swamps, canefields, low pine woods, canebrakes, cedar brakes, moist woodlands and flood plains, and open areas with little understory *1101,882,858,11623*. Stumps and logs are prefered *1023*. They also inhabit creek bottoms, rocky ridges, cultivated and overgrown fields, under the floors of deserted cabins, thickly wooded areas, and areas full of fallen logs and weeds *946,1100,11623*. It likes higher ridges that adjoin river swamps *1023*.

AQUATIC/TERRESTRIAL ASSOCIATIONS: Individuals are occasionally killed by deer, sheep, dogs, hogs, and red-tailed hawks. Juveniles are known to be eaten by chickens and turkeys *9286,10760*. Humans are the major predator of this species *11623*.

For a summary on the life history and ecology of the southeastern population (i.e. canebrake rattlesnake), see the 2011 Canebrake Rattlesnake Conservation Plan.

References for Life History

- 882 - Conant, R., 1958, A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of the United States and Canada east of the 100th Meridian, 366 pgs., Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, MA

- 1023 - Williamson, G.M., Linzey, D.W. (Ed.), 1979, Canebrake rattlesnake from the Proceedings of the Symposium on Endangered and Threatened Plants and Animals of Virginia, pg. 407-409,, 665 pp pgs., Ext. Div., VA Tech, Blacksburg, VA

- 1100 - Klauber, L. M., 1972, Rattlesnakes , 2nd ed., Vol. 1, 740 pgs., Zoological Soc. San Diego, Univ. Calf. Press

- 1101 - Mitchell, J. C., 1974, Snakes of Virginia, Virginia Wildl., Vol. 35, Num. 2, pg. 16-19

- 9286 - Terwilliger, K.T., 1991, Virginia's endangered species: Proceedings of a symposium. Coordinated by the Virginia Dept. of Game and Inland Fisheries, Nongame and Endangered Species Program, 672 pp. pgs., McDonald and Woodward Publ. Comp., Blacksburg, VA

- 10760 - Mitchell, J. C., 1994, The Reptiles of Virginia, 352 pgs., Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC

- 11623 - Savitzky, A. H., C. E. Peterson, 2001, Personal Communication, Expert Review for GAP Analysis Project, Old Dominion University

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Male Guarding

Males will often defend their mate from other males,

but we have never seen it to this extreme.

This 5ft.

male is literally curled-up and sitting on the female.

You can barely see the edge of the 4ft. female under him.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amherst

Appomattox

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Bland

Botetourt

Buckingham

Clarke

Craig

Fauquier

Floyd

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Grayson

Greene

Henry

Highland

Loudoun

Madison

Montgomery

Nelson

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Russell

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Warren

Washington

Wise

York

CITIES

Chesapeake

Hampton

Newport News

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Verified in 42 counties and 5 cities.

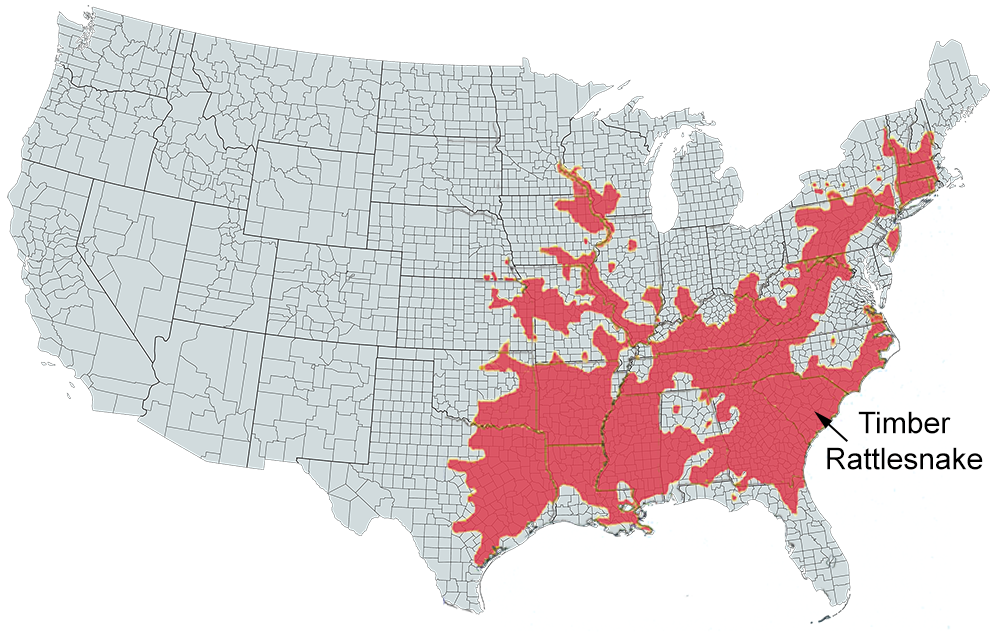

U.S. Range

US range map based on work done by The Center for North American Herpetology (cnah.org) and Travis W. Taggart.