Woodland Box Turtle

Terrapene carolina carolina

Common Name: |

Woodland Box Turtle |

Scientific Name: |

Terrapene carolina carolina |

Etymology: |

|

Genus: |

Terrapene is derived from Native Americans (Algonquin) which means "turtle". |

Species: |

carolina is derived the Carolinas, were the species was first described. |

Subspecies: |

carolina is derived the Carolinas, were the species was first described. |

Average Length: |

4.5 - 6 in. (11.5 - 15.2 cm) |

Virginia Record Length: |

6.1 in. (15.6 cm)> |

Record length: |

7.8 in. (19.8 cm) |

Systematics: Described originally as Testudo carolina by Carolus Linnaeus in 1758, based on museum specimens from "Carolina." Schmidt (1953) restricted the type locality to the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina. The combination Terrapene carolina was first used for this species by Bell in 1825. The genus Cistudo was used for this species by early authors in the Virginia literature (Agassiz, 1857; Drowne, 1900). Based on molecular and morphological evidence, Butler et al. (2011, Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 102: 889–901) concluded that the Gulf Coast Box Turtle (formerly T. c. major) represents an intergrade population between the Woodland Box Turtle T. c. carolina and the Pleistocene Box Turtle (formerly T. c. putnami). They recommended that the name T. c. major only be applied to the Pleistocene form, and that additional study of the Gulf Coast populations is warranted. However, in an analysis of a single mitochondrial gene and a single nuclear gene, Martin et al. (2013, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 68: 119–134) found support for a western (including triunguis, mexicana, and yucatana) and an eastern group (carolina, baurii, and major, plus coahuila) within T. carolina. They recommended that the former be elevated to species status (T. mexicana, the oldest name) with three subspecies. Because of the lack of concordance between the results and conclusions of Martin et al. and Butler et al., the heavy reliance on mtDNA in both studies, and the value of preserving stability, we refrain from making additional changes until more data are available. A review of the variation in this genus appeared in Dodd (2001, North American Box Turtles, Univ. Oklahoma Press, Norman).

Description: A moderate-sized terrestrial turtle reaching a maximum carapace length (CL) of 198 mm (7.8 inches) (Conant and Collins, 1991). In Virginia, known maximum CL is 156 mm, maximum plastron length (PL) is 147 mm, and maximum body mass is 603 g.

Morphology: Carapace elongated, high-domed (helmetlike), and not serrated along posterior margin; single middorsal keel prominent on 2d to 4th vertebral scutes; posterior margin of carapace flared in some adults; usually marginals 12/12, pleurals 4/4, and vertebrals 5-variation is in number of vertebral scutes; plastron 86-103% of CL; two hinges present on plastron, forming moveable anterior and posterior lobes; bridge absent.

Coloration and Pattern: Carapacial color usually brown, sometimes black, with a highly variable pattern of orange to yellow lines, spots, or blotches; ventral surface of marginals brown to black, with variable amount of orange or yellow pigment in some individuals; plastral color varies from black to brown, with or without an irregular pattern of cream to yellow; skin of head, neck, and legs brownish to nearly black with orange to yellow spots, streaks, or blotches. The upper jaw has a distinct beak, especially in older adults. The plastral hinges enable the turtle to completely enclose itself in the shell.

Sexual Dimorphism: Box turtles lack strong sexual size dimorphism. Adult males average 132.4 ± 11.2 mm CL (112.7-155.9, n = 41), 126.8 ± 8.9 mm PL (106.6-142.6, n = 44), and 383.4 ± 80.5 gbody mass (250-603, n - 41). Adult females averaged 130.1 ± 10.2 mm CL (110.4-151.5, n = 59), 126.7 ± 10.2 mm PL (95.5-147.0, n = 59), and 421.5 ± 89.3 g body mass (258-621, n = 53). Sexual dimorphism index was -0.02. The posterior lobe of the plastron is concave in males, whereas it is flat or slightly convex in females. In adult males, the carapace is flatter on the dorsum, wider, and has flared marginals compared with adult females. The claws of the hind feet in males are short, robust, and curved; they are long, slender, and straight in females. Ernst and Barbour (1972) noted that males have longer and thicker tails than females. This is an unreliable secondary sex characteristic because of the variation. Precloacal distance in males was 4-13 mm (ave. = 8.9 ± 3.7, n =7) and in females was 0-11 mm (ave. = 4.3 ± 2.6, n = 29). The color of the iris is sometimes considered indicative of a turtle's sex, but it is not always reliable. In 169 females from Prince William County, 80% had brown eyes, 10% red-brown, 7% red, and 3% golden; whereas in 86 males, 90% had red eyes, 5% brown, and 5% red-brown (Drotos, 1974).

Juveniles: Hatchling Woodland Box Turtles from throughout Virginia were 27.0-37.4 mm CL (ave. = 32.3 ± 2.3, n = 105) and 21.0-32.6 mm PL (ave. = 28.8 ± 2.3), and weighed 5.0-10.1 g (ave. = 8.0 ± 1.3). Allard (1948) reported that hatchlings from the northern Virginia and the Washington, D.C., areas were 30-33 mm CL and 26-30 mm PL, and weighed 5.7-7.7 g. The carapace is brown with a prominent yellowish keel in vertebrals 2-4. Each pleural scute has a yellowish spot and each marginal is tipped in yellow. The plastron is yellowish with an irregular brown blotch in the center. The long tail is striped yellow and brown.

Confusing Species: Glyptemys muhlenbergii is small, lacks a plastral hinge, and has reddish to orange patches behind the eyes. Glyptemys insculpta has a and black smudges along the outer edges of the plastral scutes. Kinosternon subrubrum has 11 marginal scutes and the pectoral scute on the plastron is triangular in shape.

Geographic Variation: The largest individuals in Virginia are from the southern Blue Ridge Mountains in Floyd County. Considerable variation is found in the six subspecies in shell shape and size (Ernst and Barbour, 1989a).

Biology: The terrestrial Woodland Box Turtle is found in many types of wooded areas, including hardwood forests, mixed oak-pine forests, pine flatwoods, maritime oak forests, hardwood swamps, and agricultural areas. Individuals are occasionally found in caves (Cooper, 1961). They enter water readily, but only temporarily for summer aestivation, drinking, or dispersal. Drotos (1974) reported an activity period of 5 May to 31 October for a northern Virginia population; 49% of his observations were in June. All Virginia records are March-December; 91.3% are May-September. Woodland Box Turtles respond to hot, dry conditions by seeking concealment in pools of water, mud, or damp ground (Werler and Mc- Callion, 1951; Wood and Goodwin, 1954). They overwinter buried several centimeters in the soil beneath leaf piles and grass clumps (Wetmore, 1920). The carapace of some overwintering turtles becomes incompletely covered with soil and as much as one-third of the shell may be exposed (Wetmore, 1920; Allard, 1948). Box turtles from Ohio can tolerate freezing of as much as 58% of their body water and remain frozen for as long as 3 days without injury (Costanzo and Claussen, 1990). They emerge from hibernation in Missouri when subsurface temperatures have been at or above 7°C for 5 days (Grobman, 1990). In South Carolina, the body temperature of an overwintering Woodland Box Turtle may not fall below 0°C (Congdon et al., 1989). These comparisons suggest that there may be differing activity patterns of overwintering Woodland Box Turtles in the southeastern and mountainous regions of Virginia.

Woodland Box Turtles are omnivores. The following list of natural Virginia prey has been assembled from Braun and Brooks (1987) and my observations: fruits-blackberries (Rubus spp.), mayapples (Podophyllum peltatum), elderberries (Sambucus canadensis), sweet low-bush blueberries (Vaccinium vacillans), maple-leaf viburnums (Viburnum acerifolium), muscadine grapes (Vitis rotundifolia), white mulberries (Morus alba), wild strawberries (Fragaria virginiana), black cherries (Prunus serotina), and wineberries (Rubus phoenicolasius); animals-slugs, terrestrial snails, beetles, grasshoppers, caterpillars, flies, Dusky Salamanders (Desmognathus spp.), Slimy Salamanders (Plethodon glutinosus complex); and mushrooms. Captive Woodland Box Turtles eat a wide array of food offered. This includes tomatoes, cantaloupes, mulberries, bananas, apples, plums, commercial grapes, earthworms, June beetles, mealworms, cockroaches, and hamburger (Allard, 1948; Braun and Brooks, 1987; J. C. Mitchell, pers. obs.). Ernst and Barbour (1972) summarized animal prey and plants from non-Virginia locations. The ability to completely enclose the shell affords the Woodland Box Turtle considerable protection from some predators. However, rats (Rattus spp.) and hogs (Sus scrofa) are known to kill adults (Ernst and Barbour, 1972). Eggs are eaten by domestic dogs, skunks (Mephitis, Spilogale), raccoons (Procyon lotor), foxes (Urocyon, Vulpes), crows (Corpus spp.), and ants. In other parts of the range, juveniles have been eaten by Eastern Copperheads (Agkistrodon contortrix) (Murphy, 1964) and Northern Cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) (Klimstra, 1959). The most important predators of Woodland Box Turtles are humans, who kill hundreds each year on Virginia's highways. The most vulnerable period is on summer mornings, especially after a rain.

Woodland Box Turtles throughout Virginia lay a single clutch of eggs each year. Clutch size was 2-7 (ave. = 4.1 ± 1.3, n ~ 36). Allard (1948) reported clutches of 2-7 for turtles from northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. Natural mating, which occurs on land, has been observed on 3 May, 11 and 20 August, and 2 October (J. C. Mitchell, pers. obs.; W. H. Martin, pers. comm.). C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) noted mating in Fairfax County 22 April to 30 September, and clutch sizes of 3-7 (ave. = 4.6, n = 16). Minimum known size at maturity is 95.5 mm PL for females and 106.6 mm PL for males. Delayed fertilization in Woodland Box Turtles from the Washington, D.C., area was reported by Ewing (1943). Mating behavior as described by Evans (1953) in New York consists of three phases: (1) male circles female or pushes her with a forefoot and bites edge of her carapace, (2) male mounts female and scratches her carapace with his rear claws, female opens rear of plastron, male inserts his rear claws, female clamps plastron shut pinning male's feet, male snaps at head of female or bites anterior carapace, (3) female relaxes grip of her plastron, male slides backward to rest his shell on the ground, his rear feet move forward on the edge of her plastron, she presses her rear feet on his, he positions his cloacal opening on hers and inserts penis.

Nesting occurs late May to late July, depending on elevation. I found females with shelled eggs 26 May to 25 July, 79% of which were in June. However, one female with shelled eggs in her oviducts was found after a rain in southeastern Virginia on 9 October (Mitchell and de Sa, in press). Natural nesting has been seen on 4-6 June (Dismal Swamp). Allard (1948) found nests 2 June to 14 July. Nests are dug during the day or at dusk in many soil types by excavation with the hind limbs. Cavities measured 6-8 cm deep with chambers of 7 x 10 cm (Allard, 1948). Eggs from Virginia Woodland Box Turtles averaged 35.4 ± 2.5 x 21.3 ± 1.1 mm in size (length 28.7-40.1, width 18.7-23.4, n = 147), and weighed 7.8-13.0 g (ave. = 9.8 ± 1.5). Laboratory incubation time was 56-75 days (ave. = 65.4 ± 5.2, n = 30 clutches) and hatching occurred 8 August to 30 September. Allard (1948) reported incubation times of 69-136 days in an outdoor pen and a late date of nest emergence of 21 October. In Prince Edward County, Cooke (1910) noted egg laying on 16 June and hatching on 26 August after 70-72 days incubation time. Overwintering in the nest may occur, as C. H. Ernst (pers. comm.) has found hatchlings with unhealed umbilical scars in May in Fairfax County.

The population ecology of this species has been briefly studied in Virginia but thoroughly studied in other parts of its range (e.g., Maryland: Shekel, 1950, 1978, 1989; Missouri: Schwartz and Schwartz, 1974; Schwartz et al., 1984). In a mixed hardwood forest in Prince William County, Drotos (1974) found a sex ratio of 1 male to 2 females in a sample of 255 he marked. All of his 24 recaptures were within 250 m of their initial capture site. In a mosaic of open field, hardwood forest, and marsh in Fairfax County, Bayless (1984) found a sex ratio of 1.2 males to 1 female in a sample of 50, a density of 4.4 per hectare, and home ranges of 1.2-4.7hectares. Populations of various sizes occur in many woodlots and patches of forest surrounded by agriculture and urbanization. The dynamics and demography of a sample of these need to be studied to determine the effect of habitat fragmentation.

Box turtles are notorious for living as long, or longer, than humans. An adult male with the date 1874 carved in its plastron was found in Rockingham County in August 1985 (Daily News Record, Harrisonburg), indicating an age of >111 years. It is difficult to confirm such sightings, however.

Remarks: Another common name in Virginia is the dryland terrapin (Dunn, 1915a, 1918).

Abnormal Woodland Box Turtles are occasionally found, although most abnormalities are variations in scute number. A two-headed hatchling was found in Hanover County in 1979 (Richmond News Leader, March 14). They are able to recover from some remarkable injuries; several individuals I found had recovered from severe carapacial fractures.

Braun and Brooks (1987) reported that seeds of five species of plants (Jack-in-the-pulpit [Arisaema triphyllum], mayapple, pokeweed [Phytolacca americana], black cherry, summer grape [Vitis aestivalis]) had higher germination rates after passing through the digestive tract of Virginia T. Carolina. Digestion of small seeds was greater than that of large seeds. They suggested that Woodland Box Turtles are important dispersal agents for the seeds of some species of plants.

Remains of Woodland Box Turtles are frequently found in archeological digs in Virginia (e.g., MacCord, 1971). Native Americans used the shells for food containers and rattles.

Conservation and Management: The Woodland Box Turtle is one of the most commonly encountered reptiles in Virginia. However, because of the numbers killed on highways each year and because of fragmentation of populations in urban and agricultural areas, we should be concerned about the loss of reproductive adults in isolated woodlots and forest fragments. Thousands have been collected for the pet trade. Losses of even a few adult individuals could cause extirpation of local populations, especially if these populations are small to begin with (Zweifel, 1989).

References for Life History

Photos:

*Click on a thumbnail for a larger version.

Verified County/City Occurrence in Virginia

Accomack

Albemarle

Alleghany

Amelia

Amherst

Appomattox

Arlington

Augusta

Bath

Bedford

Bland

Botetourt

Brunswick

Buchanan

Buckingham

Campbell

Caroline

Carroll

Charles City

Charlotte

Chesterfield

Clarke

Craig

Culpeper

Cumberland

Dickenson

Dinwiddie

Essex

Fairfax

Fauquier

Floyd

Fluvanna

Franklin

Frederick

Giles

Gloucester

Goochland

Grayson

Greene

Greensville

Halifax

Hanover

Henrico

Henry

Isle of Wight

James City

King and Queen

King George

King William

Lancaster

Lee

Loudoun

Louisa

Lunenburg

Madison

Mathews

Mecklenburg

Montgomery

Nelson

New Kent

Northampton

Northumberland

Nottoway

Orange

Page

Patrick

Pittsylvania

Powhatan

Prince Edward

Prince George

Prince William

Pulaski

Rappahannock

Richmond

Roanoke

Rockbridge

Rockingham

Russell

Scott

Shenandoah

Smyth

Southampton

Spotsylvania

Stafford

Surry

Sussex

Tazewell

Warren

Washington

Westmoreland

Wise

Wythe

York

CITIES

Alexandria

Charlottesville

Chesapeake

Danville

Emporia

Fairfax

Falls Church

Franklin

Fredericksburg

Hampton

Hopewell

Lexington

Lynchburg

Manassas Park

Martinsville

Newport News

Norfolk

Petersburg

Poquoson

Portsmouth

Radford

Richmond

Roanoke

Suffolk

Virginia Beach

Waynesboro

Williamsburg

Verified in 93 counties and 27 cities.

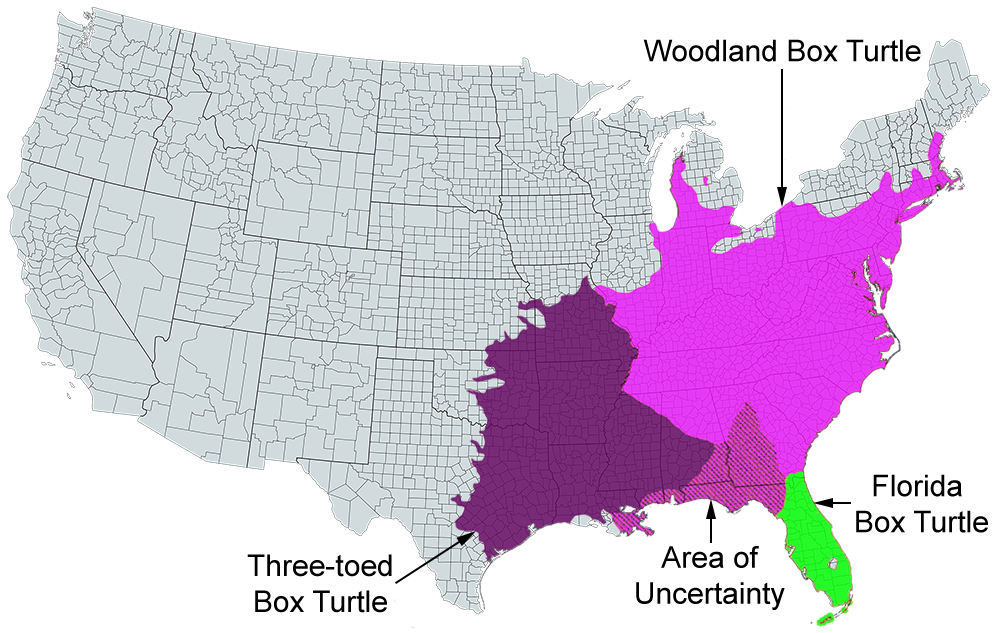

U.S. Range